Infrastructural Capture: How Big Tech’s Dependency Loop Is Reshaping American Statecraft

Infrastructural Capture: How Big Tech’s Dependency Loop Is Reshaping American Statecraft

Policy Analysis 13/2025

By Johannes Späth & Giulliano Molinero Junior

Executive Summary

This Policy Analysis examines the emergence of a self-reinforcing "privatization-dependency loop" through which major technology corporations have become structurally embedded within core functions of the U.S. federal government. Unlike historical forms of privatization, where the state contracted specific services to private actors, contemporary Big Tech firms now provide the digital infrastructure, computational capacity, and increasingly the cognitive architecture through which the state operates. This creates unprecedented forms of dependency that translate into political leverage, enabling these firms to shape subsequent rounds of policy and procurement in ways that deepen their integration into state operations.

This structural dependency is amplified by Big Tech’s influence across all stages of the policy process: from agenda-setting through research funding and algorithmic curation of public discourse, to direct legislative drafting through industry-funded fellows and revolving-door appointees, to implementation through proprietary platforms that execute government functions. The paper argues that absent strategic intervention, these accumulated dependencies risk coalescing into a path-dependent form of state capture.

For Europe, the implications extend beyond concerns about market concentration or data sovereignty. As the U.S. state becomes more tightly coupled with private technology infrastructures, European reliance on American alliance commitments faces a new uncertainty: the predictability of U.S. action may increasingly depend on the strategic calculations of a handful of corporations whose interests are not necessarily aligned with transatlantic security or democratic norms. The paper concludes that digital sovereignty, ensuring core governmental functions operate on publicly accountable infrastructure, should be elevated to the same strategic priority as energy or defense autonomy.

Insights

- THE PRIVATIZATION–DEPENDENCY LOOP IS REDEFINING SOVEREIGN POWER:

The U.S. no longer merely contracts services; it increasingly performs core executive functions through private digital infrastructures that shape what the state can know, decide, and execute. - BIG TECH’S POWER IS (INFRA-)STRUCTURAL, NOT JUST POLITICAL:

Unlike historical corporate actors, hyperscalers and AI labs control the computational, data, and communication systems through which governance itself operates. - EUROPE FACES STRATEGIC RISK THROUGH DEPENDENCE:

The deeper Big Tech becomes embedded in the U.S. state, the less Europe can rely on stable transatlantic alignment; and the more urgently it must build independent digital capabilities. Infrastructural Capture: How Big Tech’s Dependency Loop Is Reshaping American Statecraft

German executive summary:

Diese Policy-Analyse untersucht das Entstehen einer sich selbst verstärkenden „Privatisierungs-Abhängigkeits-Schleife“, durch die große Technologieunternehmen strukturell in zentrale Funktionen der US-Bundesregierung eingebettet werden. Anders als bei historischen Formen der Privatisierung, bei denen der Staat einzelne Dienstleistungen an private Akteure auslagerte, stellen Big-Tech-Unternehmen heute die digitale Infrastruktur, die Rechenkapazitäten und zunehmend auch die kognitive Architektur bereit, durch die staatliches Handeln überhaupt erst möglich wird. Daraus entstehen neuartige Abhängigkeiten, die sich in politische Hebelwirkung übersetzen und es diesen Unternehmen erlauben, nachfolgende Runden von Politikgestaltung und Auftragsaufgabe in ihrem Sinne zu beeinflussen – und so ihre Integration in staatliche Abläufe weiter zu vertiefen.

Diese strukturelle Abhängigkeit wird durch den Einfluss von Big Tech über alle Phasen des Politikprozesses hinweg verstärkt: von der Agenda-Setting-Phase durch Forschungsfinanzierung und die algorithmische Kuratierung öffentlicher Diskurse, über die direkte Mitwirkung an Gesetzgebungsprozessen durch industriefinanzierte Fellows und "Revolving-door"-Ernennungen, bis hin zur Implementierung von Politik über proprietäre Plattformen, die staatliche Funktionen faktisch ausführen. Die Analyse argumentiert, dass diese kumulierten Abhängigkeiten, sofern keine strategischen Gegenmaßnahmen ergriffen werden, in eine pfadabhängige Form der Staatsvereinnahmung münden können.

Für Europa reichen die Implikationen weit über Fragen der Marktkonzentration oder der Datensouveränität hinaus. Je stärker der amerikanische Staat mit privaten Technologieinfrastrukturen verflochten ist, desto größer wird eine neue Unsicherheit für die europäische Sicherheits- und Bündnispolitik: Die Vorhersehbarkeit amerikanischen Handelns könnte zunehmend von den strategischen Kalkülen einer kleinen Zahl von Konzernen abhängen, deren Interessen nicht notwendigerweise mit transatlantischer Sicherheit oder demokratischen Normen übereinstimmen. Die Analyse kommt zu dem Schluss, dass digitale Souveränität, also die Sicherstellung, dass zentrale staatliche Funktionen auf öffentlich verantwortbarer Infrastruktur beruhen, denselben strategischen Stellenwert erhalten sollte wie Energie- oder Verteidigungsautonomie.

Zentrale Erkenntnisse

- DIE PRIVATISIERUNGS-ABHÄNGIGKEITS-SCHLEIFE DEFINIERT STAATLICHE SOUVERÄNITÄT NEU:

Die USA vergeben nicht mehr lediglich punktuelle Staatsaufträge, sondern führen zentrale exekutive Funktionen zunehmend über private digitale Infrastrukturen aus, die (mit-)bestimmen, was der Staat wissen, entscheiden und umsetzen kann. - DIE MACHT VON BIG TECH IST (INFRA-)STRUKTURELL, NICHT NUR POLITISCH:

Im Unterschied zu historischen Unternehmensakteuren kontrollieren Hyperscaler und KI-Labore heute die Rechen-, Daten- und Kommunikationssysteme, durch die staatliche Regierungsführung überhaupt erst erfolgt. - EUROPA IST STRATEGISCH DURCH ABHÄNGIGKEIT GEFÄHRDET:

Je tiefer Big Tech in den amerikanischen Staat eingebettet ist, desto weniger kann Europa auf eine stabile transatlantische Abstimmung vertrauen und desto dringlicher wird der Aufbau eigenständiger digitaler Fähigkeiten.

Keywords: Big Tech, state capture, transatlantic relations, AI, US governance, privatization, oligopoly, digital sovereignty.

Introduction

In 2010, tech-billionaire Peter Thiel sketched a vision that would come to define Silicon Valley’s evolving posture toward the state: politics could be bypassed, he argued, and the world could be reshaped “unilaterally through technological means” (Thiel 2010) rather than through democratic persuasion. Technology, in this framing, was not simply an economic sector but an alternative route to political power; an infrastructure that could reorder society without ever winning a vote. Two decades later, this logic has become evident in the architecture of American governance. The United States increasingly executes essential state functions through the systems, platforms, clouds, and datasets of a handful of private corporations from Silicon Valley. What began as market-driven privatization has hardened into a deeper structural entanglement in which Big Tech’s infrastructures become indispensable to the state’s capacity to act.

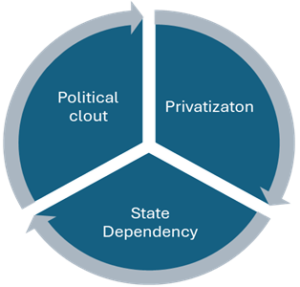

Across research, policy design, legislation, implementation, space operations, cloud computing, and now artificial intelligence, a self-reinforcing loop has emerged: public agencies outsource complex functions to technologically superior private actors; that outsourcing generates dependencies; dependencies create political leverage; and leverage enables those same actors to secure even greater influence over the next round of outsourcing. We call this self-reinforcing cycle the privatization-dependency loop. In practice, this has shifted critical levers of statecraft, such as perception, analysis, communication and deployment, into private hands, eroding the boundary between public authority and corporate capability.

This analysis traces how this loop has taken root, how it now shapes key domains of U.S. governance, and what its continuation implies for democratic control and the United States’ geopolitical reliability. It shows that the issue is no longer limited to market concentration or regulatory failure: Big Tech’s infrastructures have become entwined with the executive capacities of the American state itself. This raises the prospect that, absent strategic intervention, outsourced pockets of sovereignty may increasingly coalesce into a slow, path-dependent form of state capture. The implications extend well beyond U.S. domestic politics, touching the stability of alliances and the resilience of democratic governance in Europe and beyond.

Privatizing the American State

Privatization has traditionally been understood in two principal ways: as a shift from the public to the private sphere, and as a shift from the collective to the particular. The first highlights the way privatization reduces the obligations of transparency that states owe to their publics. Whereas governments must justify secrecy, usually in terms of national security or administrative discretion, private firms can routinely invoke commercial confidentiality to shield information (Hellman et al., 2000). The second centers on responsibility for the common good: private actors, unlike the state, are not bound by democratic accountability or broad public-interest obligations (Starr, 1988). Yet in practice, the line between public and private has always been blurry, with organizations occupying intermediate positions rather than fitting cleanly into either category (Mitchell, 2011).

In the decades following World War II, states grew to meet expanding social demands, a development that spurred a neoliberal response (Obinger et al. 2018). Neoliberalism sought not only to roll back this expansion by relocating functions to the private sector, but to create and sustain market structures conducive to permanent outsourcing (Mitchell, 2011). Neoliberalism quickly gained traction among the political and economic elites of the new world, as its promises were deeply rooted in foundational ideas of the American identity, such as the empowerment of individuals, greater efficiency, and freedom from an overreaching state (Starr 1988). This political and administrative project, built around contracting, managerialism, and dependence on external expertise, laid the groundwork for the infrastructural entanglements that define the present digital era.

Neoliberalism advanced claims of privatization, which refers to the movement of state functions into private hands, the delegation or outsourcing of service delivery, infrastructure, or decision-support systems (ibid. 1988). Notwithstanding, however similar, privatization and state capture (by private actors) are not the same. State capture refers to the movement of decision-making power into private control, whether through influence over regulations, agenda-setting, informational dominance, or institutional leverage (Hellman et al. 2000). While privatization can create conditions conducive to capture, the two are analytically distinct.

When the Public Goes Private: Historical cases of Privatization

Privatization of statecraft in the U.S. context is nothing new. Historical forms of privatization show that the U.S. frequently relied on private actors when lacking capital, expertise, or administrative capacity. A prominent example is the United Fruit Company, which in the early twentieth century operated as a quasi-sovereign power across Central America. It built railways, ports, and communications networks; controlled vast tracts of land; and intervened directly in the politics of several countries (Bucheli 2005). United Fruit acted as an outsourced arm of U.S. geopolitical and economic strategy, shaping regional development to secure trade routes and resource flows (Chomsky 1999). Its authority rested on the belief, later echoed in neoliberal doctrine, that proprietary control and business discipline offered superior reliability compared to state bureaucracies.

Major oil corporations represent another form of early privatized power. From the early twentieth century into the Cold War, firms such as Standard Oil, BP, and Royal Dutch Shell exercised quasi-governmental authority in resource-rich regions. They built infrastructure, organized extraction regimes, negotiated treaties, and influenced military and diplomatic decisions (Chandler, 1977). The “Seven Sisters” consortium’s 75-year concession in Iraq effectively ceded sovereign control of the country’s oil to foreign firms. These companies also helped normalize corporate managerial practices inside U.S. governance, contributing to the rise of New Public Management (ibid. 1977).

Domestically, oil companies shaped political outcomes through agenda-setting, informational control, and extensive informal networks. As primary sources of technical and geopolitical information, they frequently framed the very issues governments sought to regulate (Mitchell 2011). Their economic leverage over energy prices, employment, and investment further amplified their influence (Yergin 1991). Yet despite their clout, the U.S. was never structurally dependent on these firms in the way it is today on digital platforms; there was no systemic vendor lock-in, nor were these companies embedded inside the state’s core operational capacities.

The Next Frontier: How Privatization Evolves Beyond Its Historical Roots

Although the state has long relied on private actors, Big Tech creates forms of dependency that go far beyond earlier privatization. Neoliberal outsourcing supplied the administrative tools, such as contracts, public-private partnerships, and managerial logics, that made it routine for states to rely on private infrastructures. Big Tech extends this arrangement into an era where infrastructure, knowledge production, and operational capacity are all mediated through private platforms.

First, Big Tech wields cross-sectoral infrastructural power. Where United Fruit controlled logistics in specific foreign regions and oil majors dominated particular resource sectors, Big Tech firms provide the digital and physical backbone of governance itself: cloud services, compute, data pipelines, communication networks, AI systems, sensor arrays, and even strategic physical assets such as undersea cables, data centers, or launch facilities. Their infrastructures stretch across every policy domain simultaneously. A contrast captures the shift: whereas United Fruit executives complained about Washington bureaucrats, today Big Tech firms often function as the bureaucratic machinery: the systems through which states communicate, store records, analyze information, and implement policy.

Second, Big Tech introduces epistemic domination. Historically, opacity reflected deliberate secrecy: selective disclosure, market manipulation, or control over informational flows. Today, opacity also stems from the inherent complexity of digital systems, especially AI. These technologies are so technically intricate and rapidly evolving that oversight agencies cannot meaningfully audit or replicate them. This technical opacity is why such systems were outsourced to private actors in the first place, and it now deepens reliance: governments depend on Big Tech not only for infrastructure but for understanding the world through mapping, classification, prediction, threat assessment, and public discourse itself.

Third, Big Tech is integrated into state operations in ways unprecedented in earlier eras. Historically, private actors influenced states from the outside. Today, many public functions, such as communications, data storage, decision-support, identity verification, and logistical coordination, run inside private systems. Policy implementation increasingly depends on proprietary platforms, making Big Tech part of the state’s operational core rather than an external contractor.

These three dynamics form a state-capture loop unique to the digital era. As governments outsource core functions to Big Tech, they become dependent on private infrastructures, expertise, and knowledge systems. That dependence expands firms’ political influence, which in turn facilitates further outsourcing. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle in which privatization produces structural conditions for state capture, and state capture reinforces the demand for more privatization.

Figure 1: Privatization-State Dependency Loop

This dynamic also reflects what Hardin (1968) termed a “commons crisis”: a situation in which private actors pursue benefits that impose diffuse risks on the public. In the digital realm, those risks take the form of deep infrastructural dependency, opaque decision-making, and vulnerabilities embedded within the very systems the state relies upon.

Crucially, earlier forms of privatization did not generate this loop. The U.S. was never dependent on United Fruit to run government functions, nor on oil companies to operate its administrative machinery. Historical firms wielded influence over the state; Big Tech is woven into the state’s cognitive, infrastructural, and operational architecture.

In sum, what distinguishes Big Tech from earlier corporate power are three interlocking novelties: (1) cross-sectoral infrastructural power that embeds private systems across all domains of governance; (2) epistemic domination, in which the state relies on Big Tech to understand and interpret social and political reality; and (3) operational integration, where public functions run on proprietary private platforms. Together, these transformations make today’s feedback loop between outsourcing and political power historically unprecedented. This policy analysis aims to assess this self-perpetuating loop between Big Tech and the American state by analyzing its main structural components, starting with Big Tech’s policy influence.

Big Tech is everywhere

Big Tech has significant influence and leverage on the U.S. government throughout all phases of the policy process, ranging from problem identification and formulation to the drafting, selection, and implementation of policy responses (Khanal, Zhang & Taeihagh 2025). The convergence of traditional corporate influence vectors with the distinctive infrastructural leverage of Big Tech has created an unprecedented portfolio of governance-shaping tools. The following chapter assess Big Tech’s influence in Washington D.C. across the various parts of the policy process, starting with problem formulation.

Problem Formulation

Ideas and discourse play a critical role in identifying, framing, and legitimizing societal issues as problems demanding a policy response. In the digital age, the information space in which these ideas and discourses compete for attention and salience isn’t a neutral canvass but rather resembles an arena whose contours, and entry points are defined by recommendation and engagement-maximizing algorithms. In a society where traditional media like print and TV are in sharp decline, and social media has become the most common news source for Americans (Newman 2025), the recommendation algorithms and community guidelines of these near-monopolistic platforms have become key arbiters of the visibility and traction of public issues. A secondary effect of Big Tech’s control over information infrastructures is the adaptive pressure it places on traditional media organizations, which increasingly tailor their content to fit the affordances and ranking logics of dominant platforms. This dynamic grants platforms two additional layers of influence: first, by designing and continuously adjusting recommendation algorithms, firms like Meta and Google indirectly shape the tone, format, and emotional valence of journalistic content; and second, their privately governed community-guidelines and monetization rules can serve as informal mechanisms of discipline, discouraging narratives that conflict with corporate or political interests. Together, these mechanisms deepen the platforms’ epistemic and agenda-setting power in democratic information ecosystems.

However, Big Techs agenda setting capabilities extend far beyond social media. Another prominent influence avenue is spending big on research. In 2024, the parent companies of Google and Facebook, Alphabet and Meta, along with Microsoft and Apple, were the world’s largest corporate investors in Research & Development (R&D), each allocating tens of billions of dollars annually (Buntz 2024). Alphabet’s R&D budget alone exceeds that of Volkswagen, the world’s eighth-largest corporate spender, by more than double. Through these massive investments, these firms not only sustain their dominance in innovation but also gain substantial influence over research agendas and the policy frameworks that emerge downstream, particularly in the field of artificial intelligence. Research spending can come in a variety of ways, ranging from sponsoring promising talents at universities to funding whole scientific fields. Big Tech’s spending on AI research gives it a dominant position in this field.

For example, a 2021 study found that the majority of tenure-track faculty at four major U.S. universities who disclosed funding sources had received support from Big Tech (Abdalla & Abdalla 2021). Big Tech also has the funds to hire the world’s best talents. Meta, Google, OpenAI and others offer the most promising AI researchers multiple year contracts in the hundred-million dollar-compensation range, comparable to top NBA stars (Issac, Tan and Metz 2025). By offering compensation packages that substantially exceed academic salaries, leading technology firms can attract elite research talent under employment arrangements that may align research priorities, including work on AI safety and governance, more closely with corporate strategic interests than would typically occur in independent academic or public-sector research environments.

Moreover, these corporations directly sponsor entire research centers at universities, further entrenching their presence in the academic ecosystem, as exemplified by Amazon’s partnership with Columbia University (Evarts, 2020). While the full extent of this influence remains difficult to quantify, it raises a clear conflict of interest: can research outcomes truly remain independent when they challenge the financial or strategic priorities of their funders?

Corporate research operates under fundamentally different incentives than academic inquiry. The case of Timnit Gebru, a leading AI ethics researcher dismissed from Google after raising concerns about the company’s practices and presenting unfavorable insights on the safety of Large Language Models (LLMs), illustrates how internal dissent and critical findings can come into tension with corporate interests (Wakabayashi 2020). Furthermore, unredacted filings in a lawsuit by U.S. school districts against Meta and other social media platforms, indicate that Meta shut down internal research into the mental health effects of Facebook after finding causal evidence that its products harmed users’ mental health (Horwitz 2025).

These examples serve as cautionary tales of how Big Tech’s dominance in research funding may shape not only what questions are asked but also which answers are allowed to be heard.

Moreover, governments and researchers increasingly depend on Big Tech’s proprietary datasets to understand and address digital-era challenges, effectively positioning these firms as knowledge gatekeepers. Because access to granular platform data is restricted, empirical study of issues such as online misinformation, algorithmic bias, or labor market disruption often relies on the selective data-sharing practices of companies like Meta or Google. This dependency grants platforms substantial epistemic power. They determine what can be known about their own societal impact and on what terms.

Policy Process

Corporate tech firms have increasingly placed their staff or funded technologists in key public-sector roles via “tech fellowships,” advisory boards and secondments into legislative or regulatory offices, thereby gaining direct access to the mechanisms of policymaking. For example, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) rapid-response cohort of AI fellows in Congress is funded in great part by companies such as Microsoft, Google and Nvidia, placing technically seasoned staff in offices shaping AI regulation (Bordelon 2023).

Meta, Amazon and Alphabet also comprise three of the four biggest, individual corporate spenders in terms of lobbying the US government in 2024 (Open Secrets 2025).

Through revolving-door dynamics and campaign finance incentives, Big Tech has managed to have their “champions” inside areas of the policy process most directly affecting their business interests. The creation, amendments to and ultimate passing into law of the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act (GENIUS act) illustrates these dynamics neatly. This act, signed into law by Trump the 18.07.2025, regulates the issuance of so-called stable coins by private entities (S. 1582, 119th Cong., 2025). Stable coins are crypto currencies which are pegged to a traditional currency, meaning in the US context, one stablecoin usually equals one US Dollar. Through this vehicle, private actors are able to issue their own currencies and effectively serve as private banks, arguably creating a second, parallel, private banking network. A second bill, very likely to be signed into law this year still as currently attached to the must-pass National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), bans the Federal Reserve of issuing its own stablecoin pegged to the dollar (Field 2025). By eliminating the public alternative, the state elevates private stablecoins into de facto official digital dollars, despite their issuance being driven by profit rather than public mandate. Because these coins rely on public financial backstops to maintain their peg, the public absorbs the financial risks while private issuers capture the gains. This dynamic entrenches a privatized hierarchy of money creation that can be interpreted as monetary feudalism (Varoufakis 2025).

Big Tech’s fingerprints are all over these two bills. The industry long sought to issue their own stablecoins but so far had to drop their ambitions due to regulatory trouble, primarily with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) (Boorstin 2019). The CFPB feared that allowing Big Tech to issue dollar-pegged tokens would create concentrated payment networks with weak consumer protections, privacy risks, and acute “run” vulnerability if reserves or redemption mechanics failed (Chopra 2021).

The GENIUS Act now solves these headaches for the industry. The bill strongly reflects public advocacy points made by Trump’s AI and Crypto Czar, David Sacks (Sigalos 2025). Sacks, a well-connected Big Tech billionaire, is closely associated with Peter Thiel and Elon Musk as part of the original, now infamous, “PayPal Mafia”. Moreover, the chair of the Financial Services Committee that issued a blueprint for the bill is a close Silicon Valley ally, whose generous campaign contributions, helped Representative French Hill get into his position in the first place (Goodman & Mueller 2025).

The legislation contains specific exemptions ensuring that X (formerly Twitter), owned by Elon Musk, falls outside the scope of even minimal regulatory requirements. Beyond these targeted exclusions, the bill incorporates language that effectively removes the CFPB’s jurisdiction over stablecoin regulation. This is particularly significant given that the CFPB has been actively investigating payment systems operated by Meta and similar technology firms, applying banking-style regulatory standards to these platforms (Goldstein 2025). Meta owner Mark Zuckerberg complained about the CFPB being too nosy against his companies on the Joe Rogan Podcast at the beginning of 2025 (Zuckerberg 2025) and Elon Musk publicly called for its elimination (Stratford 2024). Under the Trump II administration the bureau has been severely downsized in its mission and capabilities, among other factors suffering a nearly 90% reduction in its staffing (Megerian 2025). Read through the lens of the privatization-dependency loop, the GENIUS Act illustrates how Big Tech leverages policy influence to privatize a core state function, money issuance, while shifting systemic risk onto public balance sheets, thereby deepening governmental reliance on privately operated digital payment infrastructures.

Policy Implementation

Policies and public programs increasingly rely on private cloud services, large-scale data analysis and high-powered computing for their implementation. That provides Big Tech firms with structural leverage: by providing the infrastructure underpinning modern governance, they effectively become indispensable executors of state functions. Their control over data pipelines, computing capacity, cloud-based AI tools and analytic platforms transforms them into a kind of hybrid actor, part enterprise, part quasi-administrative authority. This growing entanglement between state and corporation reshapes sovereignty: governments depend on, and are constrained by, the very private infrastructures they deploy to deliver policy (Javadi 2025). These companies possess technical knowledge, operational control, and switching costs that give them leverage in ways traditional government contractors never had. They’re making architectural decisions that shape what’s possible, what data can be linked, how algorithms classify citizens, and what privacy protections are technically feasible. This is a form of power that looks more like governance than contracting.

The Trump II administration heavily employs Big Tech to implement its policies. For example, we can see this play out in the field of migration control and deportations. Having promised the “largest deportation” in U.S. history (Trump 2024), big tech plays a key role in implementing this policy. Agencies like U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have already awarded contracts to major tech-infrastructure providers such as Peter Thiel’s Palantir Technologies. For example, in April 2025 ICE signed a US$30 million contract for “ImmigrationOS,” a platform designed to integrate multiple government and commercial databases to streamline deportations (Limon 2025). Complementing data-fusion platforms are AI-powered surveillance and biometric tools such as facial recognition, social-media and communications monitoring, geolocation tracking and mobile-device forensics, which agencies are increasingly using to identify, locate, and flag migrants. The combination of large-scale data ingestion, real-time analytics and predictive algorithms transforms what once might have required mass manpower into something computationally manageable. In this sense, Big Tech becomes indispensable to the execution of state policy. Without this infrastructure, scaling deportations to the magnitude promised would be logistically far more difficult, costly, and slow. Their technology does not just support enforcement but underpins it. This dynamic underscores a new form of public-private entanglement: private corporate platforms and services function in quasi-administrative roles for government, making Big Tech de facto executioners of policies. What we see in immigration enforcement is merely symptomatic of a deeper shift in which governments outsource the very machinery of governance, granting Big Tech quiet but sweeping influence over policy implementation in fields ranging from social services to policing, public health, and beyond. Especially visible is the privatization-state dependency loop in the fields of space exploration and exploitation as well as in cloud computing and associated capabilities. The next section will focus on these areas as key examples of the privatization-state dependency loop.

Privatization and State dependency

Patricide or how NASA was replaced by SpaceX

There can be good reasons for privatizing statecraft. One of these is outsourcing complicated and costly R&D processes to a competitive, commercial environment that tends to drive innovation and cost competitiveness. This reasoning led NASA to lobby the US congress in the early 2010s to open up space travel state-funding to private corporations. NASA’s own flagship program, the Space Shuttle, burned billions of dollars every year without achieving its desired aim: to make space travel economic and routine. In 2011 the Space Shuttle was retired (Adler 2020). A vacuum that Elon Musk’s SpaceX knew to exploit in a spectacular fashion: In under ten years the company managed to slash the launch cost of space craft eleven times compared to NASA’s Space Shuttle via the unprecedented employment of reusable rockets (Pethokoukis 2024). In 2020 SpaceX made history as the provider of the first ever commercially built spacecraft to carry NASA astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). By now SpaceX is all but dominating the space travel and satellites industry. In 2024 SpaceX accounted for 83% of all the spacecraft launched globally, statal as well as private. Starlink satellites made up 65% of all operational satellites in 2024 (Petrova 2025). SpaceX’ dragon capsule and Falcon9 rocket are the primary means by which NASA brings astronauts and supplies to the ISS (Low 2025). Moreover Starship, a new rocket still in testing, will be a key part of the U.S.’ effort to bring astronauts back to the moon. Meaning that for the foreseeable future, the U.S. is very much dependent on Elon Musk’s cooperation if they want to continue launching rockets and satellites into orbit. We could see this power dynamic play out in the spat between Trump and Musk over the so-called Big Beautiful Bill (BBB), Trump’s flagship domestic policy agenda. After public and heavy criticism of the BBB by Musk, Trump publicly threatened to withdraw billions of US dollars in public funding for Musk’s companies. The latter countered by threatening to unilaterally decommission SpaceX’s dragon spacecraft, thereby severely crippling NASA’s capabilities to bring astronauts to the ISS.

The leverage that SpaceX’s dominance over a field vital to national security provides Elon Musk over Washington is hard to overstate. The over-dependence on Starlink in terms of satellite internet is recognized and feared by high-ranking military members of US allies (Jones 2023). The unilateral turning-off of Starlink for certain operations of the contracting Ukrainian army in its defense against Russia’s aggression that Musk deemed overly escalatory serves as a cautionary tale for strategic overreliance on private actors.

But also the Pentagon now seems to have understood the danger in this constellation. Aiming to strengthen their own satellite capabilities the DoD has commissioned Space X to build a new satellite network (“Starshield”) akin to Starlink but exclusively for military purposes in multi-billion-dollar contract. Unlike Starlink though, the DoD will control and own the satellites that they are paying for (Erwin 2024). Parts of the government hence recognize the need for levelling the playing field between private contractors and state agencies, due to the self-reinforcing loop of Musk’s policy influence and infrastructural leverage over the state, the balance of power is likely to be further tipped into his direction in the coming years through further privatization and indirect funneling of state funds into his companies. A case in point is the explosion of government funding that Musk has received over the last years. In total, Musk’s companies have received $38 billion from the US government (Butler et al. 2025). Of these nearly two-thirds have been promised to Musk’s businesses since 2020 only (ibid 2025). Also SpaceX’s DoD contracts in recent years have ballooned from ca 200 million dollars in revenue in 2022 to a projected 3 billion dollars in 2025 (Petrova 2025). This coincides neatly with Elon Musk’s growing clout in U.S. politics since the late 2010s. Most prominently Musk splashed out close to 300 million U.S. dollars to back Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2024 (Hawkinson 2025). Among many other privileges in Washington, Trump nominated Musk’s billionaire friend Jared Isaacman as NASA head. Isaacman has ambitious plans for NASA that contains a DOGE-like “accelerate/fix/delete” philosophy for the agency as well as establishing a Mars exploration program, mirroring a long-held Musk dream of establishing a Mars colony (Wattles 2025). And the privatization-dependency loop continues.

Cloud Warriors

Another infrastructural area of government over-dependency on private actors is found in cloud computing. Federal cloud spending is projected to grow from approximately $17 billion in fiscal year 2024 to between $30 billion and $33 billion by fiscal year 2028, reflecting agencies' strategic pivot toward commercial cloud solutions for mission-critical operations (TBR 2025). This shift gained momentum as legacy government IT systems proved increasingly costly and difficult to maintain, prompting policymakers to embrace the private sector’s cloud infrastructure as a pathway to modernization.

Yet this modernization strategy has created a profound structural dependency on a handful of technology giants. Amazon Web Services (AWS) holds approximately 32% of the cloud services market, followed by Microsoft Azure at around 23% and Google Cloud at 11% (Kolchev 2024). This oligopolistic market structure has been translated directly into government procurement patterns. The U.S. government’s annual cloud spending currently exceeds $20 billion, with Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Oracle comprising the bulk of that expenditure (Butler 2025). For the foreseeable future, core functions of the U.S. federal apparatus, from military operations to intelligence gathering to civilian administration, are fundamentally dependent on infrastructure owned and operated by these private corporations.

The intelligence community’s reliance on Amazon Web Services exemplifies the depth of this dependency. In 2013, the CIA signed a groundbreaking $600 million contract with AWS to provide cloud services for all 18 intelligence agencies, marking a radical departure from traditional IT operations for the risk-averse intelligence community (Konkel 2024). This initial partnership has since expanded dramatically. The CIA’s Commercial Cloud Enterprise contract, awarded in 2020 to AWS, Microsoft, Google, Oracle, and IBM, was estimated to be worth tens of billions of dollars (Mitchell 2020). These arrangements mean that America’s most sensitive intelligence data, the "crown jewels" of national security, now resides on commercial cloud infrastructure.

The Department of Defense faces similar dependencies. The Pentagon’s Joint Warfighting Cloud Capability contract, awarded to Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Oracle, has a ceiling of up to $9 billion through 2028 and aims to provide globally available cloud services across all security domains and classification levels (Fung 2022). AWS alone won an estimated $724 million Navy cloud contract in 2022 (Bernards 2023). The military’s ability to conduct operations at every level, from strategic headquarters to tactical edge deployments, now depends substantially on these commercial providers' continued cooperation and capability.

This dependency creates leverage that so-called hyperscalers can and do wield in Washington’s corridors of power. The structural problem extends beyond direct lobbying, as discussed further above, to more fundamental issues of vendor lock-in and switching costs. Federal procurement guidance explicitly warns agencies to avoid vendor lock-in by evaluating business process dependencies of cloud solutions and maintaining business continuity plans for sudden service interruptions (Kent 2018). Yet the technical reality makes such flexibility difficult. Cloud vendor lock-in occurs through proprietary technologies, integrated service bundles, long-term contracts, and complex migration processes that can cause extended downtime and substantial reconfiguration costs (Opara-Martins, Sahandi & Tian 2016). A Government Accountability Office (GAO) review found that six federal agencies faced higher costs and reduced choices due to restrictive licensing practices, including requirements to repurchase licenses for cloud use and migration fees (Nihill 2024). Once agencies build their systems around a specific hyperscaler’s architecture, extracting themselves becomes prohibitively expensive and operationally risky. The federal government has not yet articulated a concrete strategy to reduce cloud computing dependency.

Federal IT leaders cite avoiding vendor lock-in as a top priority, with exclusive use of single-cloud environments expected to decline from 60% today to 35% within three years (Walshak 2024). However, this shift toward multi-cloud strategies does not fundamentally alter the underlying dependency; it merely distributes risk across multiple private actors rather than reducing reliance on them.

The political economy reinforcing this dependency follows a familiar pattern. Cloud providers including Oracle, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have offered the US government substantial discounts, in some cases up to 75%, on cloud computing services (Butler 2025), making government agencies increasingly cost-dependent on these arrangements. As agencies migrate more systems and data to commercial clouds, the switching costs compound, the institutional knowledge shifts toward vendor-specific platforms, and the political constituency favoring continued relationships strengthens. The loop is self-reinforcing: dependency creates lobbying power, which shapes procurement rules, which deepens dependency. We can also see this play out in the vital field of AI. Donald Trump issued two executive orders in this regard: “Winning the AI Race” and “Accelerating Federal Permitting of Data Center Infrastructure”. Both further entrench federal dependence on hyperscalers by streamlining the construction of privately owned data-center infrastructure by easing access to federal land, permitting, and incentives.

This dynamic raises fundamental questions about democratic governance and national security. When core governmental functions, from intelligence analysis to military command and control to civilian administration, operate on infrastructure controlled by private corporations whose primary obligation is to shareholders rather than citizens, the traditional separation between public authority and private economic power becomes blurred. The hyperscalers are not merely contractors providing a service; they have become essential infrastructure providers whose cooperation is indispensable to state capacity itself. Whether through intentional leverage or simple market dynamics, this concentration of infrastructural power in private hands represents a qualitative shift in the relationship between the American state and the technology sector.

AI and the New Architecture of American Statecraft

If the past two decades saw the outsourcing of the state’s “muscles” (launch capacity, cloud computing, satellite connectivity, data engineering) the coming decade concerns the outsourcing of its “nervous system.” Artificial intelligence marks the point at which Big Tech shifts from being the infrastructure on which the state operates to the substrate through which the state perceives, analyses, and enacts decisions. The implications are more profound than those of any prior technological shift because AI fuses three forms of power that were previously distinct: data-power, computational-power, and cognitive-power.

AI systems depend on the very infrastructures that a handful of firms already control: hyperscale cloud, proprietary data, large-scale computed clusters, and model-training pipelines. Thus, AI does not create a new dependency; it intensifies an existing one. The state’s strategic reliance on SpaceX for launch capacity and on AWS, Microsoft, and Google for cloud computing is only the prelude. With AI, those same firms are becoming the interpreters of information, the classifiers of populations, the “judgment layer” through which public agencies view the world. If cloud made Big Tech the backbone of state operations, AI makes them the eyes, ears, and, in an important respect, the brain of the American state.

Federal agencies have already begun integrating AI into mission-critical workflows. Intelligence agencies use large-scale language models for summarization, translation, entity extraction, anomaly detection and link analysis (Caballero & Jenkins 2025). Law-enforcement agencies are procuring predictive analytics tools and real-time computer vision systems (Policing Project 2024). Civil agencies, from the IRS to HHS, are testing AI triage, fraud detection, benefits adjudication, and automated regulatory compliance checks (Bryant 2025, Leddy 2025, Konstantynovsky & Sauchik 2025). In each case, the model is not an interchangeable commodity. It is anchored in a specific provider’s cloud environment, data architecture, APIs, and proprietary tool chain. That design is not accidental: hyperscalers and AI labs deliberately structure their offerings to maximize institutional lock-in. Some have gone further in offering federal agencies discounted or even free access to powerful models to make themselves the default operating system of public administration (Shapero 2025). In doing so, they are trading short-term revenue for long-term dependency.

Vendor lock-in in AI is deeper than in cloud computing because it is cognitive rather than merely infrastructural. The state does not just run its workloads on a vendor’s servers; it increasingly adopts the vendor’s categories, embeddings, taxonomies, and operational heuristics. The model becomes the grammar of decision-making. Switching providers would mean retraining personnel, recreating data pipelines, revalidating outputs, rebuilding workflows, and rewiring institutional logic (Wang, Li & Jia 2025). The cost is not financial alone; it is epistemic. Once agencies internalize a model’s ways of abstracting and structuring information, alternative representations become harder to imagine, let alone implement.

This dynamic accelerates the privatization–dependency loop. As agencies deepen their use of AI, their demand for high-performance compute rises sharply, pushing more workloads into the clouds of Amazon, Microsoft, and Google. Those same providers then gain the situational awareness to shape procurement, standards, and regulatory design. Their internal researchers dominate academic conferences; their staff populate advisory boards; their preferred technical framings shape legislative language. Meanwhile, agencies become reliant on their models, their computing, and their interpretive frameworks, giving Big Tech quiet veto power over what the state can execute at scale.

AI thus represents a qualitative shift: it collapses the traditional divide between infrastructure and governance. When the tools that store data also classify it, interpret it, and generate recommendations, the corporations providing these tools acquire hybrid authority: part engineering, part epistemic, part executive. They do not merely host the state’s functions; they increasingly mediate its understanding of the world. In the long arc of state–corporate relations, this is a structural inflection point. The question is no longer whether the American state depends on Big Tech, but to what extent Big Tech is becoming an integrated part of the American state itself.

What follows is a strategic dilemma: unless the U.S. develops public AI capabilities, open standards, or sovereign computing capacity, governance will tilt further toward a model in which essential functions of judgment, prediction, and coordination are performed by actors whose ultimate loyalties lie with shareholders or profit maximation rather than citizens. Like the age of United Fruit or the Seven Sisters, this new era blurs sovereignty, but with a difference: this time, the core resource is not land or oil, but the cognitive machinery of government itself. AI is not an adjacent policy arena; it is the next frontier of state power and its privatization. These profound changes in the workings of U.S. governance have direct implications for allies depending on Washingtons’ reliability as a security provider.

Implications for Europe

The structural features of the U.S. political system, which allow economic power to translate rapidly and effectively into political influence, have created an environment in which the country’s largest private corporations and their billionaire owners exercise an historically unusual degree of sway over Washington. As shown throughout this paper, Big Tech now exerts influence across all stages of the policy process. This enables the sector to carve out pockets of authority precisely in the areas most consequential for its business models and future revenue streams. Profits which can then be reinvested into lobbying, political financing, public-relations campaigns, and regulatory shaping.

Through this dynamic, and through the uniquely strategic products and capabilities the sector provides to the federal government, these firms have embedded themselves ever more deeply into the machinery of the American state. In doing so, they create areas of operational and infrastructural dependency; dependencies that further increase their political leverage. Under stable political and economic conditions, this privatization-dependency loop reinforces itself with every cycle, gradually shifting the balance of power toward the private custodians of essential state functions.

The resulting concentration of financial, infrastructural, and data power raises a profound question: at what point do accumulate “pockets” of outsourced sovereignty begin to cohere into a slow, path-dependent form of state capture? Even though Big Tech’s expanding influence is currently receiving more scrutiny, the momentum for meaningful policy intervention has slowed significantly from the Biden administration to the current one. As demonstrated in this analysis, the issue extends well beyond the domain of market power, which is comparatively straightforward to regulate. Big Tech’s reach has already penetrated the epistemic and executive layers of the state: the “body” and increasingly the “brain” of governance. Reversing or even moderating this trajectory would require either a deliberate, long-horizon state strategy capable of withstanding fierce corporate resistance or a disruptive break so radical that it would resemble institutional amputation. Neither option is particularly likely to emerge in the short to medium term. Moreover, high international tensions and the AI race the U.S. perceives itself to be in create urgency around national competitiveness. Combined with trust and legitimacy deficits in U.S. democracy that reduce public resistance toward executive action and technocratic fixes, these factors are likely to further accelerate the outsourcing of key state functions in the name of progress and survival.

A further consequence of this trajectory is its corrosive effect on democratic legitimacy. As more executive functions migrate into private infrastructures, the mechanisms through which citizens traditionally hold governments accountable weaken. Electoral control presupposes that the state itself possesses the capacity to act on political mandates; yet when core functions from data processing to communications, from battlefield intelligence to regulatory enforcement, depend on proprietary systems owned by private actors, elected officials lose both operational autonomy and oversight leverage. This shift replaces political accountability with technical dependency and exposes public decision-making to forms of private governance that are opaque, un-auditable, and insulated from democratic scrutiny. In effect, democratic control over the executive shrinks precisely at the moment when the executive’s reliance on non-democratic actors grows. Thereby creating a legitimacy deficit that cannot be solved through elections alone, because the levers of state action increasingly lie outside the realm of democratic contestation.

For Europe, none of this is comforting.

First, Big Tech has long objected to European regulatory ambitions and often frames core elements of the European project such as the rule of law, digital rights, competition policy and media pluralism as obstacles to its interests. Second, the deeper the entanglement between Big Tech and the U.S. state, the less predictability and reliability Europe can assume from Washington in terms of alliance politics. Profit maximization, not strategic alignment, becomes the decisive variable. Third, the same dependency-capture dynamics visible in the U.S. may increasingly take root in Europe. We already observe multiple vectors: aggressive Brussels lobbying, political financing and ideological influence, “advisory” roles in EU institutions, think-tank funding, philanthro-lobbying, media and platform ownership, and the use of AI and social media infrastructures in ways that shape the political environment (Ingram & Horvath 2025, Kroet 2025, Radsch 2025). Also, open antagonism is observable: After his social media platform X has been fined by the EU for 120 million dollars, Elon Musk has called for the bloc to be abolished (Nicol-Schwarz 2025).

What Europe needs is a sober recognition that non-state actors, Big Tech most of all, can exert strategic influence comparable to state adversaries. Their interests may be legitimate from a corporate perspective, but they are not aligned with the long-term goals of European democracy, sovereignty, or security. A strategic response must therefore elevate digital sovereignty to the same plane as material or military sovereignty. European dependence on foreign digital infrastructures may, due to the privatization-dependency loop, in the long run, prove more destabilizing than dependence on foreign gas ever was.

To be sure, Big Tech is not a monolith. The sector is riven by internal competition, corporate rivalries, and distinct strategic visions. Yet these firms share common incentive structures, overlapping business models, and broadly similar ideological orientations. It is these shared incentives, not any coherent conspiracy, that shape their expanding influence on both sides of the Atlantic. Recognizing this is the first step toward crafting a viable strategy to protect European autonomy in an era of increasingly privatized statecraft.

This requires developing genuinely European digital capabilities in cloud, computing, data governance, and AI as well as reducing structural reliance on foreign technology providers. The goal is not autarky but resilience: ensuring that the core command systems of European governance are not outsourced to actors whose incentives are fundamentally external to Europe’s democratic project. Denmark’s Office of Digital Affairs’ decision to migrate its office structure from Microsoft to Linux, an open-source platform, may be a pathbreaking way forward (Bonifield 2025). The reason for the migration was explicitly digital sovereignty as elaborated by Digitalization Secretary Caroline Stage: “[…] we must never make ourselves so dependent on so few that we can no longer act freely. Too much public digital infrastructure is currently tied up with very few foreign suppliers. This makes us vulnerable.”

Downloads