NATO is safe, but for how long? What needs to be taken from the Hague Summit (24-25 June 2025)

NATO is safe, but for how long? What needs to be taken from the Hague Summit (24-25 June 2025)

Policy Analysis 8 / 2025

By Sophie Draeger & Loïc Simonet

Keywords: The EU, NATO, Transatlantic relation, Ukraine, the U.S.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Hague NATO Summit was a success – on the paper. Mark Rutte’s first test as Secretary-General may have avoided the chaos of Trump’s first term, but the outcome reveals deep contradictions in the Alliance. The agreed 5% defence spending target is historic and the final communiqué strikingly short, yet these moves mask rather than resolve NATO’s structural vulnerability. Trump’s transactional view of Article 5 remains the Alliance’s Damocles sword, as America’s long-term commitment to Europe remains in question.

The EU, meanwhile, is facing a strategic and identity crossroads. While Trump’s pressure spurs long-overdue momentum toward a stronger European defence posture, it also risks accelerating Europe’s militarization at the expense of its founding peace project. The 'phoney transatlantic bargain' – Europe promises to spend, Trump promises to stay – may hold for now, but cannot guarantee NATO’s credibility in the long run. Amid economic risks and political fragmentation, the EU must act fast to assert its own roadmap, including tying EU funds to defence efforts and planning for U.S. retrenchment. Without this, Europe may find itself simultaneously more militarized and more vulnerable.

KEY FINDINGS

- The summit’s lean five-paragraph communiqué reflects both political pragmatism and strategic ambiguity. It avoids divisive language but leaves key issues – China, emerging tech, force readiness – unaddressed.

- A new 5% (3.5 + 1.5) of GDP defence spending baseline is NATO’s headline deliverable, praised by Trump as a personal victory. However, flexibility in defining the “+1.5%” leaves room for political gaming and creative accounting.

- The U.S. will count Ukraine aid as defence spending. But Ukraine’s NATO prospects remain frozen – Zelensky attended, but no membership invitation was extended.

- Trump’s continued ambiguity on Article 5 undermines credibility and deterrence, despite Rutte’s assurances and the formal reaffirmation of collective defence in the declaration.

- Europe must now prepare for a coming U.S. drawdown. With a possible drop in the U.S. share of Europe’s capabilities from 44% to 30% by 2032, the EU will need to shoulder 70% of Europe’s defence burden.

- European unity remains fragile. Spain and Slovakia resisted the 5% target, while Trump hinted at retaliatory trade measures. Macron decried the contradiction of demanding higher spending while escalating trade tensions.

- NATO’s Asia-Pacific partners, the so-called AP4 — Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea — were prominently involved into the Hague meeting. But the four neutral Western European Partners (WEP4 Austria, Ireland, Malta and Switzerland) still remain in NATO’s limbo.

- Austria, and other traditionally neutral or fiscally ‘frugal’ states, risk marginalization as ‘concentric circles’ of defence cooperation solidify around the Weimar+ format. A new European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) may further shift the centre of gravity.

- The Summit exposed the fragile balance of the current Atlantic compact: a mutual performance of commitment, hiding diverging interests and strategic mistrust. NATO’s deterrence now depends as much on political will as military capacity.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Der NATO-Gipfel in Den Haag war ein Erfolg – auf dem Papier. Die erste Bewährungsprobe von Mark Rutte als Generalsekretär mag das Chaos der ersten Amtszeit Trumps vermieden haben, doch das Ergebnis offenbart tiefe Widersprüche im Bündnis. Das vereinbarte Ziel von 5 % für die Verteidigungsausgaben ist historisch und das Abschlusskommuniqué auffallend kurz, doch diese Schritte verschleiern die strukturelle Anfälligkeit der NATO eher, als dass sie sie beheben. Trumps transaktionale Sichtweise von Artikel 5 bleibt das Damoklesschwert des Bündnisses, während Amerikas langfristiges Engagement für Europa weiterhin in Frage steht.

Die EU steht derweil an einem strategischen und identitätspolitischen Scheideweg. Während Trumps Druck eine längst überfällige Dynamik in Richtung einer stärkeren europäischen Verteidigungshaltung auslöst, birgt er auch die Gefahr, dass die Militarisierung Europas auf Kosten seines ursprünglichen Friedensprojekts beschleunigt wird. Die „fragwürdige transatlantische Abmachung“ – Europa verspricht, Geld auszugeben, Trump verspricht, zu bleiben – mag für den Moment gelten, kann aber die Glaubwürdigkeit der NATO auf lange Sicht nicht garantieren. Angesichts wirtschaftlicher Risiken und politischer Zersplitterung muss die EU schnell handeln, um ihren eigenen Fahrplan durchzusetzen, einschließlich der Bindung von EU-Mitteln an Verteidigungsanstrengungen und der Planung für einen Rückzug der USA. Andernfalls könnte sich Europa gleichzeitig stärker militarisiert und verwundbarer fühlen.

Die wichtigsten Erkentnisse dieser Policy Analyse sind:

- Das knappe, fünf Paragraphen umfassende Kommuniqué des Gipfels spiegelt sowohl politischen Pragmatismus als auch strategische Zweideutigkeit wider. Es vermeidet spaltende Formulierungen, geht aber auf zentrale Themen – China, neue Technologien, Streitkräftebereitschaft – nicht ein.

- Ein neuer Richtwert für die Verteidigungsausgaben in Höhe von 5 % (3,5 + 1,5) des BIP ist das wichtigste Ergebnis der NATO, das von Trump als persönlicher Sieg gepriesen wird. Die Flexibilität bei der Definition der „+1,5 %“ lässt jedoch Raum für politische Spielereien und kreative Buchführung.

- Die USA werden die Unterstützung für die Ukraine als Verteidigungsausgaben anrechnen. Die NATO-Perspektiven der Ukraine bleiben jedoch eingefroren – Zelensky war anwesend, doch eine Einladung für eine Mitgliedschaft wurde nicht ausgesprochen.

- Trumps anhaltende Zweideutigkeit in Bezug auf Artikel 5 untergräbt die Abschreckung, trotz der Zusicherungen von Rutte und der formellen Bekräftigung der kollektiven Verteidigung in der Erklärung.

- Europa muss sich nun auf einen bevorstehenden Rückzug der USA vorbereiten. Da der Anteil der USA an den europäischen Fähigkeiten bis 2032 von 44 % auf 30 % sinken könnte, wird die EU 70 % der europäischen Verteidigungslast tragen müssen.

- Die europäische Einheit bleibt zerbrechlich. Spanien und die Slowakei wehrten sich gegen das 5 %-Ziel, während Trump Vergeltungsmaßnahmen im Handel angedeutet hat. Macron erklärte, es sei ein Widerspruch, höhere Ausgaben zu fordern und gleichzeitig die Handelsspannungen zu verschärfen.

- Die asiatisch-pazifischen Partner der NATO, die so genannten AP4 – Australien, Japan, Neuseeland und Südkorea – waren an der Tagung in Den Haag maßgeblich beteiligt. Die vier neutralen Western European Partners (WEP4, Österreich, Irland, Malta und die Schweiz) bleiben jedoch weiterhin in der Schwebe der NATO.

- Österreich und andere traditionell neutrale oder fiskalisch „sparsame“ Staaten laufen Gefahr, an den Rand gedrängt zu werden, wenn sich die „konzentrischen Kreise“ der Verteidigungszusammenarbeit um das Weimar+-Format verfestigen. Eine neue Europäische Strategie für die Verteidigungsindustrie (EDIS) könnte den Schwerpunkt weiter verlagern.

Der Gipfel hat das fragile Gleichgewicht des derzeitigen atlantischen Pakts offenbart: eine gegenseitige Verpflichtungserklärung, hinter der sich divergierende Interessen und strategisches Misstrauen verbergen. Die Abschreckung der NATO hängt heute ebenso sehr vom politischen Willen wie von den militärischen Fähigkeiten ab.

NATO’s 76th summit in The Hague took place on 24–25th of June at the World Forum of the Dutch capital city. It brought together the leaders of the Alliance’s 32 member countries, along with partner nations and EU representatives.

The most delicate NATO summit in years — and Mark Rutte’s first real test as secretary general -, the meeting was a key stage in the reconfiguration of the European security architecture. “This Summit will transform our Alliance”, Rutte predicted at Chatham House in London, United Kingdom, on the 9th of June.

The nightmare scenario Rutte wanted to avoid was the turbulent 2018 NATO summit in Brussels during Trump’s first term, when a video of a tense exchange with then-Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg set the tone of the entire meeting (The Washington Post, 2018). Later that same day, Trump threatened to pull the United States out of the military organization entirely if European allies did not spend more on defense. Stoltenberg’s successor strived for a short summit – two days instead of three -, held in a friendly atmosphere. Objective number one was to avoid triggering impatience from the U.S. President and keep him happy, ‘surfing’ on Trump’s self-celebrated ‘success’ in the Iran-Israel crisis. Mark Rutte’s well-known deferential approach toward Washington expressed itself in an unbridled way, rubbing the press and some allies the wrong way.

The summit’s political and military dimensions have been prepared by NATO Defense (Brussels on 5 June 2025) and Foreign Ministers’ (Antalya on 14-15 May 2025) meetings. It was also preceded by SG Rutte’s extensive behind-the-scenes diplomacy across various capitals to secure support from Allies (to the U.S. in April, to the UK in early June, to Canada as an ‘observer’ to the G7 later in that month, to Sweden on the 13th of June). Rutte’s keynote speech at Chatham House on “Building A Better NATO”, also allowed to outline Mr Rutte’s priorities for the Hague summit (Rutte, 2025a). The SG used this intervention to ostensibly warn that Russia could be ready to use military force against the Western alliance within five years and call to set up a credible defense (Rutte, 2025a). The meeting of the presidents and prime ministers from the Bucharest Nine (B9) group of NATO’s eastern flank allies in Vilnius on the 2nd of June, joined by Baltic and Nordic leaders, also allowed to forge a common line ahead of the Hague summit and to reaffirm political unity.

The right summit at the wrong time

At the arrival in The Hague, the mood was far from celebratory. This year’s summit comes at a critical moment for the Atlantic Alliance. NATO is facing the greatest crisis in its history. Donald Trump has called NATO “obsolete” (BBC, 2017). The 47th President of the United States has been a long-time critic of the U.S.’s NATO partners and said he would not defend those that fail to meet defense spending targets, directly challenging the alliance’s principle of collective defense. He has accused European countries of failing to contribute their fair share to the Alliance’s defense needs, and his administration has signaled that its strategic focus is shifting from Europe to the Indo-Pacific region. The Heritage Foundation’s Mandate for Leadership 2025, which serves as an informal blueprint for Trump’s second-term agenda, openly questions the value of current NATO burden-sharing, criticizing European members for “an inability or refusal” to address emerging threats such as Houthi attacks on commercial shipping, arguing that the U.S. once again had to “step in to fill the security vacuum”; it further frames the Alliance’s internal capability gap in stark terms, noting that the U.S. still provides the bulk of NATO’s “core defensive capabilities”(Embree & Beaver, 2025). The rift came further to the fore at the 2025 Munich Security Conference, with Vice-President Vance’s ‘MAGA’ speech giving a glimpse of ideological war and confirming that America would make no favor to its European ‘allies’. Between Europe and the United States, the rupture is deep and historic. It is now clear that the U.S. administration is openly hostile to the EU, which President Trump perceives as directed against his interests: “The EU was created to ’screw the US'”, he said. The long-term American pivot to the Indo-Pacific is now a fait accompli.

The war raging between Israel and Iran and the risks of escalation it bears could have further diverted Trump’s attention from Ukraine; just as this new crisis had turned the agenda of G7 meeting upside down. During his pre-summit press conference, a CNN journalist asked M. Rutte whether the crisis would impact the U.S.’ view of their obligations to NATO and perhaps push NATO further down the list of priorities; the SG of course denied but admitted: “no doubt it will emerge in the discussions” (Rutte, 2025d). It was ultimately not the case, as Trump joined The Hague on the crest of his ‘success’ in managing the crisis. The hope that a political settlement in Ukraine would be agreed upon before or at the summit has now faded (Antonio-Vila, 2025), which might also explain the laconic nature of the summit’s declaration when it comes to Ukraine and Russia (see hereafter).

An unusual shape for the final communiqué

As anticipated by SG Rutte, (Rutte, 2025a), the final communique of the summit has been slimmed down considerably: just five paragraphs – a stark contrast to recent summits. The 2024 Washington declaration ran to 40 paragraphs, while the Vilnius communiqué the year before stretched to a sprawling 90, covering a wide range of issues, from force posture, readiness, preparedness, and interoperability to nuclear issues, missile defense and China (Vilnius Summit Communiqué).

This year, the Allies prefered to avoid a lengthy and politically risky negotiating process on the wording of the communiqué, which could have weakened its content and opened path to divergences. This pattern was already used at the G7 meeting in Canada: the event wraped up with no final communiqué, which starkly illustrates the deepening policy divisions among leaders of the world’s most powerful economies. Contrary to the previous summits, this year there is no way, through the final declaration, to figure out how prominent issues like China, emerging technologies, space, terrorism, and technical challenges such as force readiness and the implementation of the new NATO Force Model, have been discussed in The Hague – if only they have been addressed.

Preserving Transatlantic unity

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 led to a NATO revival. “We stand together in unity and solidarity and reaffirm the enduring transatlantic bond between our nations”, the Allies hammered at the Madrid Summit of the Alliance in 2022. One of the challenges of the 2025 summit was to preserve and revive the transatlantic political link. The two-day gathering was also intended to signal to Russian President Vladimir Putin that NATO is united, despite Trump’s previous criticism of the Alliance, and determined to expand and upgrade its defenses to deter any attack from Moscow.

The Heads of State and Government gathered in The Hague “reaffirm (their) commitment to NATO, the strongest Alliance in history, and to the transatlantic bond” (Hague Summit Declaration, para. 1). Beyond Spain’s reservation about the 5% baseline (see hereafter), no strong diverging voice was heard. The European allies understood that they should not overburden the summit. The usual ‘troublemakers’ Hungary and Slovakia that not only oppose Ukraine joining NATO but are also pushing back against NATO playing a large role in coordinating military aid, remained discreet.

The Summit’s core deliverables

- Ramping-up defense spending: a new baseline

Since the Allies decided to adopt a ‘low profile’ on Ukraine (see hereafter), defense spending became the de facto centerpiece in The Hague. “As far as Washington is concerned, there’s just one main deliverable at this summit: the 5% defense spending target”, Sara Moller, associate teaching professor in the School of Foreign Service, made clear (Moller, 2025).

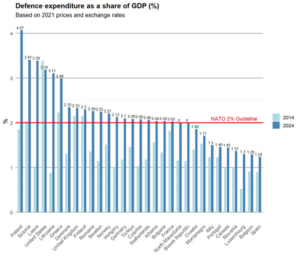

The summit took place in a context of rising global defense spending, which in 2024 reached USD2.46 trillion, up from USD2.24 trillion the previous year. Growth also accelerated, with the 7.4% real-terms uplift outpacing increases of 6.5% in 2023 and 3.5% in 2022. As a result, in 2024, global defense spending increased to an average of 1.9% of GDP, up from 1.6% in 2022 and 1.8% in 2023 (McGerty & Dewey, 2025).

Following the joint declaration signed by the presidents of Poland, Romania, and Lithuania at the B9 summit in Vilnius, on 2nd of June (President of the Republic of Lithuania, 2025), all 32 NATO allies commit to raise defense spending to 5 percent of GDP per year by 2035 (Hague Summit Declaration, para. 2) – a significant increase from the current target of 2 percent by 2025 which was agreed at the Wales summit in 2014 -. To help ‘swallow the pill’, a new “3.5 + 1.5” phased approach, conceptualized by SG Rutte way ahead of the summit and agreed by the Defense Ministers at their Brussels meeting on 5th of June, draws a distinction between two essential categories of defense investment: 3.5 percent would go towards ‘core’ defense spending, meaning ‘hard’ requirements necessary to meet the Alliance’s Capability Targets, such as weapons and artillery, while the remaining 1.5 percent would be allocated to broader military adjacent ‘defense related spending’, meaning cyber-defense, investment in military mobility, infrastructure and network protection, resilience, civil preparedness and awareness. This new baseline is developed at para. 3 of the summit declaration. Donald Trump immediately praised the agreement to raise defense spending to 5% as a “monumental victory” for his country (Connor, 2025b).

This elasticity in how to define what comprises the 5% is welcome – and a ‘face-saving’ for several member states -, but many questions remains open: what is the ‘metric’ and criteria to define exactly what should fall within the 1.5% ‘softer’ category – “inter alia” at para. 3 leaving some degree of blur -? (Brose, 2025). Behind the stage, experts fear that some member states might include bridges and traffic lights into their figures, in order to boost their chances of hitting the target on paper. How to avoid the ‘absorption capacity issue’ that SG Rutte himself mentioned in his Chatham House speech (Rutte, 2025a)? Worth being mentioned: “direct contributions towards Ukraine’s defense and its defense industry count when calculating Allies’ defense spending” (Hague Summit Declaration, para. 3).

Some members, mainly the Baltics, argued, previous to the summit, in favour of an accelerated deadline – 2030 -, given Russia’s ongoing threat, while others worried that the high target is politically and economically daunting (Diffley, 2025). 2032 was mentioned at some point, but the balance has tipped in favor of a more extended timeline, which appears in contradiction with the 5-year deadline before a possible Russian attack. Eight of NATO’s thirty-two member countries spend less than 2% of their GDP on defense (Croatia, Montenegro, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, Luxembourg, Belgium and Spain), despite this rule having been in force for almost ten years. Even the United States are not yet at 5% (3.19% in 2024). The closest member is Poland (4.07%). France is in the lower medium (2.03%). At the curve’s lowest, Belgium (1.29%) and Spain (1.24%). Whereas Sweden and the Netherlands have already committed to meeting the 5% threshold and Estonia and Poland are “very close” the target (Rutte, 2025d), a few days before The Hague, Spain rejected NATO’s 5% defense spending hike as ‘counterproductive’ and called for an exemption (Kayali & Griera, 2025). "I think it’s terrible what Spain has done," Trump reacted, adding he would deal directly with Spain and would make the country pay twice as much on trade (Connor, 2025a). Slovakia also said it would not meet the target, arguing that raising living standards and cutting its borrowing were priorities. The Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever expressed skepticism as well. At his pre-summit press conference on 23rd of June, SG Rutte played assertiveness on this point and denied that Allies, not only Spain, are free to spend as much money as they want, as long as they guarantee that they will fulfil the capability targets: it is “really important that we do this”, he hammered; “also the countries with a smaller budget need to show that at least they have the plans in place to get to the 5%” (Rutte, 2025d). However, Rutte acknowledged a degree of flexibility left to each ally to deliver on NATO commitment and meet the capability targets. Members are required to “submit annual plans showing a credible, incremental path to reach this goal” (Hague Summit Declaration, para. 3); such “credibility” seems more important than imperative goals, and Allies will be judged upon this criterium. European leaders said they wanted an orderly and gradual transition, fearful that any gaps could be exploited by Russia. More than somehow artificial metrics, what will ultimately matter is output, meaning actual military capabilities.

Data compiled from NATO’s Secretary General’s Annual Report 2024, Annex 4, pp. 50f.

The summit’s outcome on defense expenditure determines NATO’s future coherence (Diffley, 2025). The 2029 review will allow to take stock of the progress made, in light of the strategic environment and updated Capability Targets.

- Greater investment

Greater investment is needed in NATO’s core military requirements as well as additional broader defense-related investments, including infrastructure and resilience. The objective is to stimulate NATO’s adaptation and address the gaps revealed by the war in Ukraine.

The new defense investment plan adopted in The Hague is one of the key deliverables of the summit. It will be decisive to ensuring effective deterrence. While the details of national capability targets are classified, M. Rutte called for a five-fold increase in air defense capabilities, thousands more tanks and armoured vehicles and millions of rounds of artillery ammunition (Rutte, 2025d). During his visit to the UK earlier in June, Rutte also urged the doubling of NATO’s enabling capabilities including logistics, supply, transportation, and medical support.

- Building up a transatlantic defense industrial base

The defense industry plays a vital role in supporting NATO’s ambitions for enhanced regional defense and must be prepared to meet the growing demand for advanced military equipment and systems. M. Rutte, at Chatham House, confessed that boosting defense industrial production was the only question that would keep him awake at night (Rutte, 2025a). “We need a Transatlantic defense industry that is stronger, faster and more innovative”, Rutte said at his joint press conference with Czech President Pavel on 21 May (Rutte, 2025c). “The Summit in The Hague will send a clear demand signal to industry. And industry must meet our ambition”, Rutte further insisted at Chatham House (Rutte, 2025a). While these efforts are framed as national contributions, they directly feed into NATO’s collective capability targets and the credibility of its deterrence posture. Translating spending commitments into real-world capability improvements will remain the ultimate benchmark of success.

Paragraph 4 of the summit declaration is devoted to industrial cooperation:

“We reaffirm our shared commitment to rapidly expand transatlantic defense industrial cooperation and to harness emerging technology and the spirit of innovation to advance our collective security. We will work to eliminate defense trade barriers among Allies and will leverage our partnerships to promote defense industrial cooperation.”

In addition to the usual public forum and following the practice of last year’s Washington summit, a Summit Defense Industry Forum took place on 24 June, hosted by the Dutch Ministry of Defense and NATO, in cooperation with the Confederation of Netherlands Industry and Employers and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- NATO’s long-term support for Ukraine

The doubts about the war in Iran and the American intervention having been dispelled, the war in Ukraine remained the ‘elephant in the room’, including Donald Trump’s ambivalent relationship with Vladimir Putin and his difficult relationship with Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Zelensky.

Observers long feared that Zelensky would simply be excluded from the summit (Zadorozhnyy, 2025), which would have been a première since Russia’s full-scale invasion and a negative signal after the 2024 summit in Washington, at which Zelensky was a key guest. After his meeting with SG Rutte on 2 June, President Zelensky announced that Ukraine was invited to the summit. In parallel, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio denied that his country had objected inviting the Ukrainian President to the event (RBC Ukraine, 2025b). Until the last moment, rumors also floated that this year’s final declaration may not contain any direct mention of Russia and even Ukraine, which would have made the Hague meeting very different from recent summits (Jozwiak, 2025a). The same dilemma was true with regard of any wording on Russia. Despite Poland and the Baltics’ ostensible support, Kyiv had lost any hope to be officially invited to become a NATO member in The Hague.

Finally, M. Rutte was able to announce, in his doorstep speech: “Ukraine will be big at the Summit today” (Rutte, 2025e). Contrary to expectations, the final declaration states that “Allies reaffirm their enduring sovereign commitments to provide support to Ukraine, whose security contributes to ours” (Hague Summit Declaration, para. 3). It also mentions the “long- term threat posed by Russia to Euro-Atlantic security” (para. 2), without formally condemning Moscow’s operation in Ukraine. Nothing in the declaration detracts from the formulation of the 2024 Washington summit declaration – NATO "will continue to support it on its irreversible path to full Euro-Atlantic integration, including NATO membership" – which therefore still prevails. “The irreversible path of Ukraine into NATO is there, and it is my assumption, it is still there after the Summit”, M. Rutte made clear when he announced that the outcome of the summit would be limited to a “very concise list of conclusions” (Rutte, 2025a).

No dedicated NATO–Ukraine Council meeting was held this time, contrary to the last two summits. Instead, a working dinner of the Ukraine-NATO Council at the level of foreign ministers, chaired by the Deputy Secretary General of the Alliance, took place on the evening of June 24. This was the only public event with the participation of a non-NATO state. However, the bilateral meeting between Trump and Zelensky was “long and substantive”, according to the latter.

The threat of the U.S. exit recedes, but Trump’s lip service commitment to Article 5 remains as a Damocles sword

On the eve and in the wake of the Russian invasion, the U.S. deployed an additional 14,000 troops to reassure European Allies, which brought the total number of U.S. troops in Europe to nearly 100,000 (Cooper, 2022). The significant reduction of U.S. forces from NATO operations in Europe would have profound implications, at least in the short term. It would require a wholesale rewrite of NATO’s collective defense, which would need to rely increasingly on European Allies to bridge capability gaps and bolster deterrence efforts, necessitating greater coordination and significantly increased defense investment (Loorents, 2025).

When SG Rutte visited Chatham House on the 9th of June, Bronwen Maddox, Director and Chief Executive of the institution, asked him: “Can NATO survive a drawdown of US presence in Europe, and some of the questions that the US has directed at NATO about its value?”. The question was indeed on everyone’s lips. “There’s absolutely no question of that”, Rutte replied (Rutte, 2025a), also referring to the “clear commitment of the American President” regarding U.S. troops’ presence in Germany; “I have no worry about that”, Rutte said. A few weeks earlier, State Secretary Marco Rubio’s had also delivered the message that Washington remained committed to NATO (RFE/RL, 2025a). The eventual nomination of a U.S. officer to the SACEUR[1] post, confirmed just days before the summit, was presented by Rutte as a signal of continued American engagement (Stewart, Ali & Bayer, 2025). However, all this did not fully dispel the nervosity of the other Allies, nor did the shallow appearance of Matthew Whitaker, US President Donald Trump’s newly appointed ambassador to NATO, at the Lennart Conference in Tallinn on 16-18 May.

The Hague’s declaration is crystal clear: “We reaffirm our ironclad commitment to collective defense as enshrined in Article 5 of the Washington Treaty.” Beside this direct and seemingly unambiguous reaffirmation, Trump, shortly before arriving in the Dutch capital city, again promoted his transactional vision of Article 5, when he appeared to question the U.S. commitment to the Alliance’s core mutual defense clause, saying there were "numerous" definitions of it (Lunday, Traylor & Kayali, 2025). Asked to clarify his commitment to NATO’s Article 5 in the margins of his meeting with Dutch Prime Minister Dick Schoof, Trump declared: "I stand with it. That’s why I’m here. If I didn’t stand with it, I wouldn’t be here" (Connor, 2025b). This, as well as SG Rutte’s disclaimers – “there is absolute clarity that United States is totally committed to NATO, totally committed to Article Five” (Rutte, 2025e) – could not dispel ambiguity nor completely restore NATO’s credibility. While this may provide short-term reassurance, ongoing debates in Washington and the ideological direction signalled by Trump-aligned policy circles suggest that transatlantic coordination could remain vulnerable to political shifts.

Furthermore, a forthcoming U.S. drawdown from Europe is still considered by experts as inevitable. “Right now, the administration is saying all the right things about its continued commitment to Europe. But at the same time, it’s widely known that cuts to the U.S. force posture in Europe are coming, possibly as soon as this summer. That looming announcement will be front and center. Everyone will be watching closely for any signals about what, exactly, the Pentagon plans to pull from the European theater.” (Moller, 2025). Europeans should also prepare for a more disruptive U.S. approach, including sudden troop withdrawals before or after the summit, L. Fix and R. Lissner also warn (Fix & Lissner, 2025), based on a leaked Pentagon memo (Lubold, De Luce & Kube, 2025).

“A stronger European Union is also a stronger NATO”[2]

“Don’t join the NATO summit without knowing who you are”, Sven Biscop warned right before the event (Biscop, 2025b). NATO’s European Allies should have carefully considered this piece of advice.

After repeated and more and more pressing calls from Donald Trump for European countries to invest more and take greater responsibility for their defense, preserving European unity was no less important than increasing defense spending. “Europe’s will to act together is real”, Kaja Kallas, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, highlighted at a plenary session of the European Parliament dedicated to preparing for the summit, referring to the Rearm Europe / Readiness 2030 plan[3] and the SAFE mechanism[4] (Kallas, 2025).

With a broader rebalancing underway in the transatlantic security relationship, NATO–EU coordination is becoming increasingly important.[5] The meeting of the so-called ‘Weimar+’ group in Italy on 12 June already provided EU’s ‘biggest players’ (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom, joined by their counterpart from Ukraine, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte and the EU High Representative, Kaja Kallas) with the opportunity to commit to “reinforce the European contribution to NATO” and “fair burden-sharing” (Weimar+, 2025). This is not about replacing NATO – or not yet – but about strengthening its European pillar.

The new expense baseline will change the balance within the Atlantic Alliance. By 2032, the US share of conventional military capabilities in Europe is expected to drop from 44% to around 30%. This will require EU countries to shoulder 70% of Europe’s collective defense from 56 percent today – a dramatic shift (Admiral Giuseppe Cavo Dragone, Chairman of NATO’s Military Committee, quoted by Decode 39, 2025). As Liana Fix and Rebecca Lissner reveal, the U.S. direct financial contribution to NATO’s budget, which is different from the national defense spending pledge, could also shrink from 16 percent of the budget to almost nothing. A leaked White House memo suggested cutting State Department spending in half, including eliminating entirely the contribution to NATO’s budget (Lee & Amiri, 2025). Trump himself suggested the United States should not pay anything for NATO. This would leave European NATO allies with another $3.5 billion shortfall to fill (Fix and Lissner, 2025).

In that sense, the Hague summit can be interpreted in two different ways.

On the one hand, it might offer a chance to Europe, which should move further in the direction of collaborative solutions and working together. Brussels might use NATO’s new financial requirement as a powerful economic lever, particularly for countries that depend on European funds but under-invest in defense. States that fail to meet their NATO obligations could thus be denied access to European funds dedicated to innovation, energy resilience and cyber defense. The Hague Summit is also expected to foster the emergence of a European Defense Industrial Strategy (EDIS).

On the other hand, the economic impact for the Europeans is stark, with a huge part of their budget to be directed toward military expenditures, which bears the risk of a self inflicted economic and social crisis. This “would fundamentally transform European societies—turning them into nations where social justice and economic stability are subordinated to military buildup” (Dagdelen, 2025). Ultimately, the costs are borne by taxpayers. In France, where the public deficit amounts to 5,8% of the GDP and the public dept reaching 113% of the GDP, the challenge will be high, as underlined by a recent note of the Haut-Commissariat au Plan (Claeys, Moura, Trinh & Quennesson, 2025). Speaking after the summit, French President Emmanuel Macron underlined the "aberration" to demand more European defense spending while escalating a trade dispute between NATO members, urging a return to trade peace among allies. "We can’t say we are going to spend more, and then at the heart of NATO, launch a trade war," Macron said. All in all, the Hague summit might have further endangered the EU as a peace project and exacerbate the change in its DNA.

It is therefore crucial that the Europeans put forward their own roadmap, as suggested by German Minister Boris Pistorius (Balticnews, 2025) for a phased transition, and start planning as soon as possible.

Conclusion: Beyond The Hague

At first glance, the Hague summit, even shortened both in length and ambition, has not only reaffirmed transatlantic unity, but also made it more operational. Only on the paper, though. Looking closer, it was essentially what the French call a marché de dupes: a “phoney Transatlantic bargain” in which Europeans pretend they will spend 5% of their economic output on defense and Donald Trump pretends in return that he is committed to Article 5 (Taylor, 2025).

The U.S. stays, but only if Europe proves it is worth its protection. As much as President Trump and NATO Secretary General Rutte presented the new expense baseline as a win for the Alliance, the rhetoric over funding obscures a more fundamental point: NATO’s credibility as a deterrent is in question. The truth is that no amount of European defense spending will resolve the alliance’s deepening political rift—or satisfy an administration fundamentally opposed to the principle of collective defense (Benson, 2025).

“The damage is done. Because even if the US were to radically alter course and recommit fully to NATO as we knew it, everyone now knows that a next President may change it back again. The US cannot treat NATO the way it treats the agreements on climate change: it joins, it leaves, it rejoins, and leaves again. Deterrence demands constancy, or there is no deterrence. Unless it is actually tested in war, Article 5 will now never be as credible as before.” (Biscop, 2025a, 1).

[1] NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe.

[2] Kallas, 2025.

[3] The Readiness 2030 White Paper calls for mobilizing €800 billion – €150 billion through loans and €650 billion through member states’ defense spending that is now exempt from the previous EU debt limit – by the European Commission and envisions member states “closing critical capability gaps and supporting the EU defense industry,” “deepening the single defense market,” and “enhancing European readiness for worst-case scenarios.” (see https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/white-paper-for-european-defence-readiness-2030_en).

[4] Adopted in May 2025, the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) instrument is a new EU financial instrument that will support those member states that wish to invest in defense industrial production through common procurement, focusing on priority capabilities. Through SAFE the EU will provide up to €150 billion that will be disbursed to interested member states upon demand, and on the basis of national plans (see https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/05/27/safe-council-adopts-150-billion-boost-for-joint-procurement-on-european-security-and-defence/).

[5] On 10 January 2023, NATO and the EU signed a 3rd – and long awaited – joint declaration formalizing their cooperation (Simonet, 2023).

Downloads