Flawed by Design: What al-Sisi’s Egypt Reveals About the Myth of Authoritarian Efficiency

Flawed by Design: What al-Sisi’s Egypt Reveals About the Myth of Authoritarian Efficiency

Policy Analysis 9 / 2025 by Johannes Späth

Keywords: Authoritarianism, Egypt’s political economy, regime legitimation, EU–Egypt Relations, regime security, regional stability

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This policy analysis challenges the rising narrative that authoritarian regimes, despite their repressive nature, offer superior governance efficiency and contribute to regional stability. Using Egypt under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi as a case study, it argues that the perception of authoritarian efficiency is not only analytically flawed but dangerously misleading for international policymakers. European and Western engagement with Egypt continues to rely on flawed assumptions about authoritarian capacity and stability. Financial support, arms sales, and diplomatic legitimacy are extended largely unconditionally, under the illusion that al-Sisi’s regime can deliver long-term order. This approach ignores the structural fragility baked into Egypt’s political economy, and risks enabling a trajectory toward fiscal implosion and social unrest.

The paper argues for a strategic recalibration. European policymakers should shift from regime-centered engagement to resilience-centered investment, focusing on areas like education, climate adaptation, and local economic empowerment that outlast regime cycles. Europe’s current approach risks buying short-term quiet at the cost of long-term instability. A policy recalibration grounded in realism, not regime accommodation, is both necessary and overdue.

INSIGHTS

EXPECT REGIME FRAGILITY TO DEEPEN:

Despite its façade of strength, Egypt’s authoritarian system is structurally brittle. The hollowing out of institutions, reliance on opaque patronage networks, and

mounting fiscal pressure will likely accelerate political and social instability, especially as austerity deepens and international debt obligations tighten.

STOP OUTSOURCING STABILITY TO AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES:

Europe’s largely unconditional support for Egypt, based on flawed assumptions of authoritarian efficiency and regional stabilizing capacity, is backfiring. Military-led governance is fueling mismanagement and repression, not long-term order. Continued reliance on al-Sisi’s regime risks complicity in Egypt’s downward spiral.

RECALIBRATE ENGAGEMENT TOWARDS SOCIETAL RESILIENCE:

Instead of regime-centered partnerships, the EU should pivot to resiliencefocused investment: supporting education, climate adaptation, civil infrastructure, and economic inclusion. This approach is more aligned with long-term European interests and less vulnerable to authoritarian decay.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Diese Analyse stellt die zunehmend verbreitete Annahme infrage, wonach autoritäre Regime, trotz ihrer repressiven Struktur, effizienter regieren könnten und zur regionalen Stabilität beitragen. Am Beispiel Ägyptens unter Präsident Abdel Fattah al-Sisi wird gezeigt, dass die Vorstellung von „autoritativer Effizienz“ nicht nur analytisch unhaltbar, sondern für internationale Entscheidungsträger potenziell gefährlich ist. Europäische und westliche Partnerschaften mit Ägypten stützen sich weiterhin auf fragwürdige Annahmen über die Handlungsfähigkeit und Stabilität autoritärer Systeme. Finanzhilfen, Waffenlieferungen und diplomatische Aufwertung erfolgen weitgehend bedingungslos – im Irrglauben, das Regime al-Sisis garantiere langfristige Ordnung. Dabei wird die strukturelle Fragilität der ägyptischen Politökonomie übersehen, die mittelfristig in eine fiskalische Schieflage und soziale Unruhen münden könnte.

Die Analyse plädiert daher für eine strategische Neuausrichtung. Europäische Politik sollte sich von einem regimezentrierten Ansatz hin zu investitionsgeleiteter Resilienzförderung bewegen, etwa in den Bereichen Bildung, Klimaanpassung und lokaler wirtschaftlicher Teilhabe. Das derzeitige Vorgehen mag kurzfristige Ruhe erkaufen, gefährdet aber langfristig Stabilität und europäische Interessen. Eine realistische, nicht an autoritäre Machterhaltung angepasste Politik ist überfällig.

WESENTLICHE EMPFEHLUNGEN

DIE FRAILITÄT DES ÄGYPTISCHEN REGIMES WIRD WEITER ZUNEHMEN:

Hinter dem autoritären Ordnungsversprechen des ägyptischen Regimes verbirgt sich ein strukturell fragiles System. Die Aushöhlung staatlicher Institutionen, wachsende Abhängigkeit von intransparenten Patronagenetzwerken und eine rapide Verschärfung der Haushaltskrise deuten auf zunehmende soziale Spannungen und politische Destabilisierung hin.

AUTORITÄRE REGIME GARANTIEREN KEINE STABILITÄT:

Die europäische Unterstützung für Ägypten basiert auf überholten Annahmen über Effizienz und Stabilität autoritärer Herrschaft. Tatsächlich fördert das militärisch dominierte Regime Missmanagement, Repression und langfristige Unsicherheit. Eine an der Systemerhaltung orientierte Außenpolitik droht, europäische Interessen in der Region zu unterminieren.

EU-ENGAGEMENT AUF GESELLSCHAFTLICHE RESILIENZ AUSRICHTEN:

Statt autoritäre Führungen zu stützen, sollte sich die EU auf Investitionen in Bildung, Klimaresilienz, soziale Infrastruktur und lokale wirtschaftliche Teilhabe konzentrieren. Eine Resilienz-orientierte Partnerschaft stärkt langfristig Stabilität und ist weniger anfällig für das Scheitern repressiver Systeme.

In recent years, a curious shift has taken root in global political discourse: a growing fascination, among policymakers, pundits, and broad segments of the public, with the perceived decisiveness and long-term strategic capacity of authoritarian regimes. Is authoritarianism, beyond moral considerations, the more efficient and effective governance system after all? A growing number of people seem to believe that. The 2024 edition of the of the “Perceptions of Democracy” survey conducted by International IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) found that in 8 of the 19 countries surveyed[1], more people have favorable views of a ‘strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament or elections’ than have unfavorable views. Worryingly, there was no country surveyed in which a majority of respondents have ‘extremely unfavorable’ thoughts about non-democratic leadership (IDEA 2024).

Authoritarian systems are increasingly depicted as streamlined, future-oriented machines, able to bypass the institutional gridlock, partisan paralysis, short-termism, and the lengthy, inclusive decision-making processes that seem to afflict liberal democracies. This certain admiration, often couched in pragmatic terms, reflects a broader narrative: that authoritarianism, despite its normative drawbacks, may hold functional advantages in a time of waning global security, economic instability, and geopolitical flux.

This narrative is not only analytically flawed—it is politically dangerous. What appears on the surface as efficiency often conceals deeper dysfunctions. Authoritarian regimes may at times indeed move quickly, but the quality, sustainability, and accountability of those decisions remain profoundly compromised. Centralized power structures, opaque decision-making, informal hierarchies, and rule by fear tend to distort information flows, paralyze middle-tier institutions, and generate a political economy driven more by elite preservation than by national interest. Rather than being models of forward-thinking governance, such systems are frequently reactive, fragile, and structurally inefficient beneath their surface-level discipline.

This Policy Analysis aims to challenge the uncritical readiness, domestically and internationally, to accept authoritarian governance by examining one of its most emblematic contemporary cases: Egypt under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Positioned as a key strategic ally of Europe, the United States and Israel, Egypt is often described by Western partners as a “pillar of regional stability” (EU commission 2024). And yet, Egypt offers a textbook example of the systemic limitations and contradictions inherent in authoritarian governance as well as the dangers of Europe’s long-standing strategy of treating authoritarian regimes as reliable partners in maintaining regional stability, particularly in its approach to its southern neighborhood. By using Egypt under al-Sisi as a case study, this analysis exposes the internal incoherence, elite anxiety, and patronage-driven logic that define authoritarian governance and systematically undermine both domestic capacity and foreign policy coherence.

At its core, this analysis contests the enduring myth of authoritarianism as both an effective and efficient provider of domestic policy solutions and as a stabilizing force in international affairs. It argues that what is often mistaken for state strength is more accurately described as regime rigidity; what is framed as strategic foresight is frequently the product of informalism, personalism, and repression. Egypt’s case reveals not a lean, top-down machine but a fractured system riddled with fear, opacity, and a striking misalignment between the regime’s survival strategies and the country’s long-term interests.

Understanding the true nature of authoritarian systems is not merely an academic exercise. It has profound implications for how Western democracies engage with these regimes, structure foreign aid, and define their own democratic values. As this paper will argue, the cost of misreading authoritarian governance is not only strategic; it is normative, and ultimately self-undermining.

The Structure of Authoritarian Rule in Egypt

Understanding the limits of efficiency and effectiveness in Egypt under al-Sisi requires first outlining the state’s structure and its overlap with the regime. Differentiating between the official state structure (constitutions, ministries, legal frameworks) and the regime (military networks, intelligence apparatus, patronage systems) is vital, as the coexistence of formal and informal political processes is a key defining feature of Egyptian governance. As shall be elaborated throughout the paper, real power rests in the latter sector. The shadowy informal structure al-Sisi derives his position and power from is better conceptualized as a state within the state, rather than the two forming a coherent and unitary entity. Egypt effectively operates under a dual governance model, where formal institutions exist but real decision-making is mostly concentrated in a parallel military-security apparatus. This apparatus, however, should not be seen as a unitary actor or coherent entity either—but we will return to that point later. Even though al-Sisi in his now well over a decade long rule has shaped this dual track system significantly, he hasn’t created it. Egypt, with the partial exception of a brief period following the Arab uprisings in 2011/12, has never been a democratic state in its history.

The state and the regime

Throughout the countries’ modern history, the military and the intelligence services have been the dominant political forces, enshrining the gap between the official state structures and its nominal decision-making power and the real center of power. The post-monarchy Egyptian state following the 1952 Free Officers’ coup laid the foundation for this system. Under the rule of Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954 -1969) a military-bureaucratic authoritarian regime evolved, with the Arab Socialist Union (ASU) serving as a populist tool to keep society mobilized and attached to the regime. Over the decades under the rule of Anwar as-Sadat and later Hosni Mubarak, the system further evolved and moderately liberalized, eventually leading to a system of “managed pluralism” (Balzer 2003). This system allows for opposition (e.g., Muslim Brotherhood in parliament) only to the extent it doesn’t threaten the hegemony of the governing coalition consisting of the military-security apparatus, the dominant party and crony business elites. The overthrow of Mubarak following the Arab Uprisings in 2011 marked a turning point in the position and strategic calculus of the military-security apparatus. In the immediate aftermath, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) assumed control and formed an interim government. Initially, the military leadership sought to contain the revolution by allowing Mubarak’s strategic removal as well as the country’s first genuinely democratic elections. All the while maintaining indirect control over the incoming president through its entrenched dominance within the state apparatus. However, the unexpected electoral victory of Mohamed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate and a long-standing rival of the military, disrupted this plan. Realizing their gamble had failed—and fearing the erosion of their privileges, institutional coherence, and what they perceived as threats to national unity—the generals and intelligence chiefs, under then–Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, conspired with Gulf allies to orchestrate a counterrevolution in 2013, installing “their man” in the presidency (Mostafa 2020).

The lesson drawn by the military-security establishment was clear: Mubarak’s relative liberalization had enabled the uprising and brought the country to the brink of collapse and/or Islamist rule. In response, the post-2013 regime has pursued a strategy of tighter, more immediate control. Under al-Sisi, Egypt has undergone significant autocratization, characterized by intensifying repression, the centralization of decision-making, and the expansion of patronage networks within an increasingly narrow elite coalition.

The new constitution of 2014 provides a veneer of pluralism, but, crucially, real power remains outside these structures. The constitutional amendment of 2019 altered regulations regarding the terms of the presidency and allowed for al-Sisi to run for a third time. He won the elections in December of 2023 with 89.6 percent of the votes (Reuters 2023). Prior to the elections the regime removed potential challengers, intimidated their supporters and prevented competition (Human Rights Watch 2023). The constitutional amendments of 2019 further equipped the executive with broad and unchecked supervisory powers over the (civilian) judiciary, while the jurisdiction of military courts was significantly expanded (ICJ 2019) – essentially allowing the regime to trial any opposition in military courts, reflecting the two-tier or dual track governance in Egypt.

Moreover Law No. 13 issued in 2017 gives the president the authority to choose the heads of key judicial institutions, including: Presidents of the Court of Cassation, the State Council, the Administrative Prosecution Authority and the State Lawsuits Authority (ICJ 2019). The co-optation of the judiciary marks a significant step back from the Mubarak era where the judiciary enjoyed a semi-autonomous position and where courts could still rule against the state or government in a number of high profile cases. For example, the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) dissolved parliament twice under Mubarak in the 1980s, ruling that electoral laws violated constitutional principles of equality. The first dissolution occurred after the regime skewed representation in favor of Mubarak’s ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) (Soliman 2012). Such judicial dissent is no longer be possible under the current regime.

Similarly, ministries have been systematically stripped of their traditional bureaucratic functions, with key portfolios handed to military officers and decision-making centralized in the presidency and security apparatus. With the Foreign Ministry increasingly marginalized, the General Intelligence Service (GIS) has been elevated to serve as the regime’s primary instrument of foreign policy. While ministries under Mubarak still operated as semi-autonomous fiefdoms with some technocratic input, they now function as little more than implementation arms of military-dominated policy—mirroring the broader hollowing out of Egypt’s formal state institutions under the regime’s militarized authoritarianism. Important state positions are routinely handed to loyalists, typically from al-Sisi’s outer circle, who have a military background and frequently rotate between positions (Sayigh 2025). The military also increased its presence on the provincial governance level. At least 16 of the 27 Egyptian governates are ruled by (ex-) Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) cadres as of the last appointment of governors in July 2024 (Al-Ahram 2024). Moreover, in July 2020, President al-Sisi approved amendments to the Popular Defense Law and the Military Education Law (Laws No. 165/2020 and 46/1973), granting the Minister of Defense the authority to assign a military advisor to every governorate. These advisors are tasked with supervising and implementing local public policy (Dawn 2021).

The military and the regime

The Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) have long been a central actor in modern Egyptian political history. However, under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s rule, their role has evolved into that of an expanding political-economic force, marked by the increasing militarization of state institutions and the growth of their economic empire. This trend suggests that the EAF has gone beyond being the traditional guardian of the regime to become an active stakeholder in governance, with its influence permeating both formal decision-making structures and informal networks of patronage.

The EAF are headed by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF). The SCAF sets the goals and strategic tasks of the armed forces and oversees all military and defense matters. It is made up of around 25 high-ranking generals, each with their own specific portfolio, ranking from legal to operational, intelligence, morale, logistics, etc. (Cairo Review of Global Affairs 2012). Just days before transferring power to newly elected President Mohamed Morsi, the council issued a constitutional declaration on June 18th 2012, effectively granting itself legislative authority, broad autonomy from the civilian government, and a decisive role in shaping the new constitution through veto powers (Wenig 2014). This power is reflected in the new constitution of 2014, which leaves the crucial Minister of Defense as the only cabinet position the presidency can’t appoint at will, as the SCAF has enshrined a veto power. This grants the SCAF de facto autonomy and immunity as it is headed itself by the Minister of Defense.

At first glance, one might interpret this as evidence that the SCAF constitutes the true center of power, with al-Sisi, a former high-ranking military officer, serving as its civilian-political extension. However, the reality is more nuanced. While the SCAF undoubtedly wields significant authority, the power dynamics under al-Sisi reflect a complex interplay between institutional military interests, presidential autonomy, and the broader structures of Egypt’s authoritarian system. Al-Sisi’s ability to consolidate personalist rule, coupled with the EAF’s deepening economic entrenchment, suggests a symbiotic yet contested relationship rather than a straightforward subordination of civilian leadership to military command.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial for deciphering the logics of governance in contemporary Egypt, where formal state institutions, military hegemony, and presidential power intersect in ways that defy simplistic categorizations. The SCAF and the presidency are entangled in a mutually supporting and benefitting governance network or power-sharing mechanism. Yet they are simultaneously competing for hegemony and pursuing diverging interests in many fields, further complicating and obscuring decision-making processes. In short, the relationship between the two power centers is characterized by mutual dependence, both sides need each other.

Al-Sisi serves as the civilian face of military dominance, providing a veneer of civilian-democratic legitimacy to the military’s pervasive influence in Egypt’s political and economic spheres. His presidency ensures the continuation of the military’s privileged position without the need for direct governance, which could attract domestic and international scrutiny. Conversely, al-Sisi’s authority is critically underpinned by the support of the SCAF. The military’s backing is crucial for maintaining internal stability and suppressing dissent, which are essential for al-Sisi’s continued rule. The SCAF’s control over significant economic resources and its influence within the state apparatus provide al-Sisi with the tools necessary to implement his policies and sustain his governance model. Without the military’s endorsement and cooperation, al-Sisi’s capacity to govern effectively would be significantly diminished, especially given the fact that civilian institutions have either been co-opted or hollowed out.

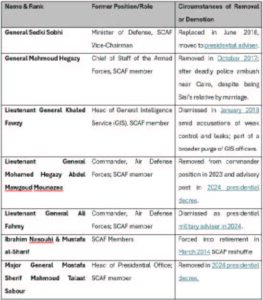

As both the presidency and the SCAF are mutually dependent for their continued dominance, they also possess the means to undermine one another—a fact that injects a constant undercurrent of tension into Egypt’s governance structure. President al-Sisi, through his highly personalized control of the powerful General Intelligence Service (GIS or Mukhabarat), holds considerable leverage over the military elite. His prior role as head of Military Intelligence from 2010 to 2012, during the tumultuous period of the 2011 revolution and its aftermath, further suggests that he likely possesses significant kompromat on key figures within the armed forces. In addition, al-Sisi has consolidated his control over the EAF through his dominance over senior promotions and routine purges of potential rivals from influential military and bureaucratic positions (see Table 1). He gained the power to control promotions through the 2014 constitution. Conversely, the SCAF has secured a formal constitutional prerogative to intervene in governance whenever it deems the state or constitution to be under threat. A provision introduced through constitutional amendments that al-Sisi in 2019 himself endorsed to extend his own term limits. This apparent quid pro quo underscores the delicate balance of power and the dual character of authoritarian rule in modern Egypt.

This dual character, cooperation in maintaining regime survival and competition in shaping its direction, creates a fragmented and opaque decision-making environment. It undermines the notion of a top-down, coherent authoritarian apparatus and instead reveals a system where informal bargaining, overlapping mandates, and intra-elite rivalries often dictate outcomes. This reality deviates sharply from the image of a unified, technocratically efficient authoritarian regime. Rather, it is better understood as a hybrid form of authoritarian pluralism within a militarized framework which is centralized, but not monolithic. While democracies are often criticized for slow decision-making due to coalition politics and competing interests, similar dynamics exist in authoritarian regimes, albeit in far less transparent and regulated forms. These opaque intra-elite negotiations frequently prioritize regime cohesion and personal power over national policy goals, making them arguably even more misaligned with the public interest than in democracies.

Table 1 High-ranking SCAF members purged or sidelined by al-Sisi

Mechanisms of Dysfunction: How the System Undermines Itself

The complexity of policy making in Egypt is further compounded by the regime’s dual-track governance model, where formal institutions are systematically hollowed out and replaced by informal networks, as well as by pervasive repression, legal ambiguity, kleptocratic exploitation of state resources, and a chronic lack of meritocratic recruitment. These dynamics not only hinder coherent policymaking but also undermine both domestic and international legitimacy. The following chapter will unpack these features in detail, examining how they shape and often distort the functioning of the Egyptian state under al-Sisi.

Patronage and Institutional decay

Egypt’s economic and governance landscape is increasingly dominated by a handful of military-affiliated companies that repeatedly benefit from state contracts, preferential treatment, and opaque allocation of public resources. These same entities appear across a range of key policy areas, from infrastructure to welfare and strategic commodity imports. This pattern reveals not only the militarization of service delivery but also the deep erosion of civilian institutional authority under the logic of authoritarian governance.

A striking example is Egypt’s subsidy reform under President al-Sisi, which ostensibly aimed at improving fiscal efficiency. Between 2014 and 2024, the regime implemented sweeping cuts to fuel and bread subsidies without first establishing a robust social safety net, thereby exacerbating poverty. Meanwhile, military-affiliated industries were spared the same austerity measures. Instead, subsidies were redirected toward politically strategic groups, such as military-run bakeries selling bread via ration cards, demonstrating how loyalty management took precedence over equitable, technocratic policymaking. To mitigate the social fallout among Egypt’s poor, al-Sisi created the "Future of Egypt" organization by presidential decree. Formally affiliated with the Air Force, this welfare and agriculture agency now operates a national network of retail outlets that sell basic goods below market prices, effectively replacing civilian welfare mechanisms. Despite the Air Force’s lack of agricultural expertise, it was granted control over the reclamation of 1.5 million acres of land. The organization’s role has since expanded to include forcible land seizures and, more critically, the strategic import of key staples such as wheat; A responsibility formerly held by the civilian Ministry of Supply (Ezz 2024).

A similar pattern is evident in the infrastructure sector. The Armed Forces Engineering Authority (al-Hay’a al-Handasiyya) has become the country’s largest contractor, monopolizing public works projects without competitive bidding or parliamentary oversight. Legal amendments in 2013 and 2016 enabled direct state assignments to military entities, bypassing both private sector competition and public accountability. The Wataniyya Company for Road Construction and Development, another military-owned firm, controls thousands of miles of toll roads, collecting fees outside any transparent budgetary framework (Ibrahim 2020).

These examples are not isolated. They reflect a broader governance model in which state institutions are systematically sidelined, hollowed out, or co-opted by military-run entities. Military-affiliated companies remain shielded from financial audits and legislative scrutiny, allowing them to operate a vast off-budget economy. As a result, technocratic planning bodies are marginalized, public wealth is reallocated into informal circuits controlled by the armed forces, and institutional competence gives way to patronage-driven decision-making.

This dynamic has two major implications for assessing authoritarian rule. First, the erosion of institutional autonomy aids in maintaining regime stability but diminishes the state’s capacity for effective, evidence-based policymaking. Ministries become mere executors of top-down directives rather than sites of strategic planning. Second, the systematic elevation of loyalists, often from al-Sisi’s military-dominated inner circle, over qualified technocrats entrenches a governance model that privileges regime loyalty over institutional competence. The result is bureaucratic brittleness, policy incoherence, and a governance structure increasingly defined by personalistic control.

Beyond administrative erosion, authoritarian governance also exerts direct political pressure on state institutions. A clear case is the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), which delayed a critical currency devaluation under presidential pressure to maintain an artificially strong exchange rate for political optics (Agarwal & Mazarei 2024). This delay caused a severe dollar shortage, disrupted imports, and eroded investor confidence. When the pound was finally floated in March 2024, it lost more than 60% of its value within hours, triggering a cost-of-living crisis (Magdy 2024). The episode underscores how subordinating technocratic institutions to regime imperatives undermines macroeconomic stability in favor of short-term political gains.

The consequences of this loyalty-based, militarized governance model are reflected in Egypt’s deteriorating macroeconomic indicators. National debt quadrupled between 2010 and 2022, making Egypt the second-largest borrower from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) globally (Springbock 2022). Bloomberg ranks Egypt as the world’s second most likely country to default on its debt, after war-torn Ukraine (Ismail 2023). As political economist Timothy Kaldas remarked, “Ukraine was invaded by the Russian army, while the Egyptian economy was invaded by its [own] army” (Middle East Monitor 2023).

Private sector actors face an uneven playing field, as military-affiliated firms enjoy sweeping advantages: tax exemptions on imports, free conscript labor, access to state-owned properties, audit exemptions, and privileged access to public tenders (Sayigh 2019). This stifles competition, crowds out innovation, and contributes to the long-term stagnation of Egypt’s economic and institutional development.

Information Breakdown and Fear-Driven Governance

The economic impediments rooted in the regime’s patronage and kleptocratic logic are compounded by the dysfunctions of fear-based governance, which erode information flow and agency within state institutions. Fear serves as a mechanism of control in order to suppress dissent but also distorts bureaucratic behavior and produces systemic inefficiencies. This dynamic gives rise to two mutually reinforcing pathologies: information distortion and decision-making paralysis.

The regime’s reliance on coercion generates a culture of self-censorship within the state apparatus. Officials, wary of reprisals, systematically suppress or sanitize unfavorable reports, leaving leadership with a dangerously skewed understanding of realities on the ground. This information vacuum is compounded by risk-averse behavior at all levels of administration. Even routine decisions are often escalated to senior authorities, as mid-level bureaucrats prioritize self-preservation over effective governance (Sayigh 2025). The result is an administrative system that moves at a glacial pace, incapable of agile responses to emerging challenges.

This institutional paralysis in Egypt leads to slow, inefficient decision-making and implementation, often resulting in mal-coordinated and contradictory policies. The bloated bureaucracy, compounded by always looming security-sector vetoes and limited resources, forces lower-ranking officials to rubber-stamp decisions from above without meaningful input (Abd Rabou 2015). The cumulative effect is a state that appears strong but is increasingly hollow. One that can mobilize security forces to crush protests but struggles to implement basic public services efficiently (Allmeling 2025). When combined with the regime’s already severed feedback loops with society due to massive repression against critical media (RSF 2023), this internal decay suggests a system eroding from within, even as it maintains an outward facade of control.

The irony is self-reinforcing: the very mechanisms meant to preserve authoritarian power, centralized control and punitive discipline, ultimately weaken its ability to govern effectively. A state that cannot process bad news or delegate decisions is one that cannot adapt, leaving it vulnerable to crises of its own making.

Legitimizing Illegitimacy through Megaprojects

In al-Sisi’s Egypt, hyper-personalization of power and the regime’s legitimation strategy, positioning itself as the nation’s savior and modernizer, have led to a focus on highly visible, costly mega-projects with questionable rationales and uncertain future revenue streams or long-term payoffs.

One telling example is the already mentioned “One Million and a Half Acres” land reclamation project, launched by al-Sisi and entrusted to the military engineering authority, al-Hay’a al-Handasiyya. Promoted as a lifeline for young Egyptians and small farmers, the initiative quickly turned into a coercive campaign of land seizures, particularly in poor southern provinces like Qena. There, long-settled farmers were forcibly evicted by military personnel, accused of illegally occupying land they had cultivated for decades. The provincial governor, a retired general, oversaw the demolition of homes and farms across vast tracts, while complaints filed to the national agricultural authority, also headed by a former general, were ignored. Ultimately, the project stalled due to a lack of adequate water resources, revealing that it had been launched without a viable feasibility plan (Ibrahim 2020). Its primary function, it appears, was symbolic: to project state-led development and modernization, even at the cost of local livelihoods and in defiance of basic logistical realities.

Another striking example of the regime‘s prioritization of spectacle over substance is the New Administrative Capital, a $58 billion mega-project marketed as a solution to Cairo’s overcrowding. The project is however unlikely to have the desired outcome (Al-Kaid 2021). Featuring Africa’s tallest tower, the Middle East’s largest cathedral, and what will be the world’s largest defense headquarters, the city exemplifies the regime’s obsession with image-driven development. Oversight of the project lies with the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD). A company majority-owned by the military, which also sells housing units, ensuring direct profit to Egypt’s armed forces. Despite repeated claims that the project has cost “not a single pound” (al-Sisi 2023, Abdeen 2018) of public money, evidence shows billions in state capital injections, debt guarantees, and in-kind transfers (Taweel 2023). Key among these transfers is the handover of valuable real estate in central Cairo, such as ministerial buildings vacated by the government, to the Sovereign Fund of Egypt (SFE). Established in 2018 and controlled by the presidency, the SFE operates outside public oversight, meaning the proceeds from the sale or lease of these assets will not return to state coffers but will benefit regime-aligned interests. Meanwhile, the government will pay rent to ACUD for office space it does not ultimately own, deepening the fiscal burden while enriching a military-run enterprise. The New Capital thus starkly illustrates the militarization of economic development: a high-cost vanity project that siphons public wealth into opaque, elite-controlled structures under the guise of modernization.

A similar logic underpinned the 2015 expansion of the Suez Canal, another heavily publicized mega-project conducted by economic enterprises affiliated with the EAF, which has cost an estimated $8.2 billion for the heavily indebted country (Reuters 2024). Although the project was framed as a national renaissance initiative and funded largely through domestic bond sales, it failed to deliver the projected doubling of canal revenues. While symbolically potent, the expansion offered limited economic returns, especially in the short term, and diverted scarce public resources from more pressing developmental needs. Egypt is currently studying a further expansion of the waterway, despite falling revenues from the Canal. These megaprojects, for all their modernizing rhetoric, primarily function as vehicles for redistributing public wealth to military-affiliated companies, sustaining the regime’s patronage networks and reinforcing the loyalty of its core constituencies. This pattern reflects a broader logic of authoritarian coalition-building, in which regime survival is the overriding priority, trumping other policy goals such as adequate health care and education for its citizenry.

Egypt currently only spends 1.16 % of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare, which falls short of the constitutionally required amount (Kassab 2024). For comparison, advanced economies typically spend around 11% of their GDP on healthcare, the United States being the global outlier with 16.7 % in 2023 (Wager et al. 2025). Other, democratically run, BRICS countries such as Brazil and South Africa spend 4.1% and 5.41% respectively (WHO 2025). Similarly, for the fiscal year 2024/25 the government only aims to spend 1.7 percent of the country’s GDP on education (Human Rights Watch 2025), down from 3.9% in 2015 (World Bank 2025). Although reliable and recent data isn’t available for all states of the world, Egypt’s public education spending of 1.7% of GDP for 2024/25 likely places it among the lowest 20 countries globally. This is especially notable given that Egypt’s GDP per capita is much higher relative to many of those countries.

These meager percentual figures on public spending are likely overstated still, as they reflect an economy in which a major revenue-generating sector, the military, operates off-budget and without transparent fiscal redistribution. Hence, official spending appears more generous than what actually reaches civilian services.

As the next chapter will show, this logic of glamour over substance also extends to Egypt’s foreign policy, where decisions often prioritize regime security over the country’s broader national interest.

Enrichment over Security: Foreign Policy as Patronage in al-Sisi’s Egypt

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi dominates Egypt’s foreign policy decision-making, acting not only as the head of state but also as the de facto chief strategist and ultimate arbiter of major diplomatic and security choices. This allows the leadership to use foreign policy as a mechanism to feed the patronage machinery on which the regime relies to continuously secure the loyalty of the EAF. One concrete example of this pattern playing out in reality are Egypt’s recent weapon purchases.

Al-Sisi’s arms deals

Egypt’s status as one of the world’s top arms importers, ranking third globally between 2017 and 2021 and eighth between 2020 and 2024 (Wezeman et al. 2022; George et al. 2025), sits uncomfortably alongside its chronic macroeconomic instability and soaring public debt. At first glance, this pattern may be read as the logical outgrowth of Cairo’s volatile geostrategic environment: flanked by conflict zones in Libya and Sudan, facing persistent insurgency in Sinai, and managing the Suez Canal’s geopolitical weight. Yet closer scrutiny reveals that Egypt’s arms procurement strategy is not anchored in a coherent defense doctrine. Rather, it reflects the logics of a kleptocratic, military-dominated regime that uses security policy as both a tool of elite enrichment and a shield against scrutiny.

Since al-Sisi’s rise to power, arms deals have increasingly served as a mechanism to maintain and reward regime-aligned military elites. Take Egypt’s €5.2 billion agreement with France for 30 Rafale fighter jets in 2021, negotiated in secrecy and financed through French state-backed loans (Disclose 2021). The GIS played a central behind-the-scenes role in brokering the deals, leveraging security relationships with Western capitals, while military intelligence coordinated with the Ministry of Military Production to channel offsets into military-run companies, often without competitive bidding or external oversight (Elsobky 2021). While the Dassault-manufactured Rafales offer prestige and airpower, they are strategically redundant given Egypt’s existing fleet of U.S.-supplied F-16s. Aircraft for which Egypt already possesses trained pilots, maintenance infrastructure, and spare parts. There was also no imminent airpower threat that justifies the scale of the purchase, especially given Egypt’s highly precarious financial situation. Similarly, the 2015 purchase of two French Mistral Vessels offers little immediate strategic gain and strains state’s coffers unnecessarily (Wan Beng 2015). The rationale was less about battlefield needs and more about solidifying ties with France as a political patron while feeding the military-industrial patronage machine. Tellingly, the Rafaele deal coincided with the French TotalEnergies’ expansion in Egypt’s offshore gas, a joint venture with the state-owned Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (EGAS) (Total 2021). Under President Emmanuel Macron, France has become a central arms supplier to Egypt and the countries’ most important European investor, continuously funding al-Sisi’s house of cards, despite an increasingly abhorrent human rights track record and lacking, meaningful economic reforms (i.e. limiting the EAFs role in the Egyptian economy) (Ahram 2025).

The pattern repeats in Egypt’s relationship with Russia. In 2015, the two sides signed an initial agreement for Russian state-owned company Rosatom to build the countries’ first nuclear energy facility in Dabaa, Egypt, again backed by Russian loans. In 2017 the final contract was signed in Cairo (Deutsche Welle 2017). Between 2017 and the end of 2021 Russian arms exports to Egypt then soared by 723 per cent in comparison to the 2012-2016 time interval, while their overall acquisitions were just 73 per cent higher than in 2012–16 (Wezeman et al. 2022). Egypt and Russia have strengthened their defense ties through multiple high-value agreements, including a $3.5 billion military-technical cooperation deal covering the supply of 46 MiG-29 fighter jets and 46 Ka-52K Alligator attack helicopters. Further deepening this partnership, Russia secured a contract in May 2017 to provide Egypt with ship-based Ka-52K helicopters, designed for reconnaissance and combat operations aboard the French-built Mistral-class amphibious assault ships acquired by Cairo in 2015. Beyond arms sales, the two nations have enhanced their strategic alignment through joint military exercises conducted since 2016 (Arab Center DC 2021).

What ties these decisions together is not national security, but the regime’s need for liquidity, legitimacy, and elite buy-in. Major arms deals often function as parallel financing strategies. The Sisi regime routinely negotiates military contracts alongside infrastructure and energy deals using them to unlock credit lines or position Egypt as a stable regional interlocutor in the eyes of Western governments eager for counterterrorism partners. The result is a bloated security sector embedded in the civilian economy, while inflation surges, external debt soars, and IMF programs falter on implementation.

In sum, Egypt’s arms procurement pattern is not only a poor substitute for strategic planning, it actively undermines the state’s ability to respond to its most urgent threats. A regime addicted to securitized grandstanding and rent-seeking cannot simultaneously build a professional defense infrastructure. Instead, it manufactures the illusion of strategic capacity while hollowing out the state’s fiscal and institutional foundations. What looks from a distance like geopolitical prudence is, in practice, a cycle of militarized misgovernance.

Foreign Alliances: Regime Aid as Substitute for Strategy

Since the 2013 coup, Egypt’s foreign alliances, particularly with Gulf monarchies and Western powers, have been calibrated not around mutual interests but around regime needs. The logic is transactional: Egypt receives financial support, arms, and political backing in exchange for regional alignment, the transfer of Egyptian public assets or migrant containment.

Building on this transactional logic, the regime has increasingly resorted to liquidating Egyptian assets, land, infrastructure, ports, and strategic companies, to Gulf buyers in exchange for hard currency bailouts (see for example Diwan 2024, Schaer & Farhan 2024). These sales, often rushed and opaque, are not part of a national development strategy but rather a desperate effort to plug fiscal holes and maintain short-term liquidity. A similar dynamic plays out with the European Union: Egypt offers migration containment, effectively policing the Mediterranean for Europe, in return for cash and diplomatic indulgence (Janssen 2025). The underlying pattern is clear: regime survival trumps all else. There is no coherent long-term vision, only an escalating cycle of dependency. The more mismanagement and kleptocracy hollow out the economy, the more foreign policy becomes a tool for regime monetization. Trading sovereignty for solvency in a downward spiral of desperation.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Egypt under Abdel Fattah al-Sisi offers a cautionary tale of authoritarian governance. Despite the illusion of order, discipline, and decisiveness projected by the regime, the country’s foreign and domestic policy apparatus is riddled with contradictions, inefficiencies, and kleptocratic distortions. The very mechanisms that appear to grant authoritarian regimes a comparative advantage, such as centralization, repression, securitization, are in fact the source of chronic misgovernance, poor decision-making, and long-term instability. The Egyptian case illustrates that authoritarianism does not streamline the state; it corrodes it from within.

This insight carries clear implications for how Europe should calibrate their policy toward authoritarian partners like Egypt. The prevailing approach, which treats authoritarian regimes as reliable crisis managers and bulwarks against regional instability or irregular migration, is analytically lopsided. This view ignores the long list of structural malfunctions that at least this type of authoritarianism needs in order uphold the power of the regime. These malfunctions translate into excessive arms transfers, human rights abuses on a mass scale and an economic exploitation and mismanagement. Developments that leave Egypt’s economy starring into the abyss and put the country on a trajectory towards implosion (el-Hamalawy 2024).

European policymakers should stop treating authoritarian partners as guarantors of order and start engaging with them as sources of structural fragility. Egypt’s repression-first governance model is not producing long-term resilience but dependency, volatility, and ever-deeper cycles of asset liquidation and sovereignty trade-offs. This trajectory is incompatible with the EU’s long-term interests in a stable, prosperous, and rule-based southern neighborhood. Europe faces a strategic dilemma in its approach to Egypt: continue providing largely unconditional support to President al-Sisi’s regime in exchange for short-term stability, at the cost of enabling policies that risk long-term economic and political implosion. Or push for greater conditionality and risk alienating Cairo, potentially opening the door for rival powers to gain influence in a country of major geopolitical significance. For this reason, a calibrated approach is necessary. Instead of directly feeding the power-base of the regime via arms sells, Europe should invest in sectors in Egypt that build economic and social resilience regardless of who’s in power. These can include skills training, climate adaptation, small and medium business support, water safety or green energy infrastructure. Even though structural competition makes true international coordination regarding the continued foreign funding of Egypt’s increasingly brittle economy unlikely, tactical coordination is still possible. Through informal alignment with the IMF, World Bank, and Gulf donors to push for a shared baseline of reforms, even where interests diverge. The same applies to EU–G7 mini-coalitions, where not every actor must agree, but coalitions of the willing can still create pressure and coherence.

To effectively challenge the growing admiration for authoritarian governance, both within Europe and in its foreign policy circles, Western democracies must go beyond moral critiques rooted in human rights violations. While essential, this framing alone often fails to persuade more pragmatic audiences who see authoritarianism as “effective.” A more compelling response requires shifting the focus to how authoritarianism malfunctions as a system of governance. Authoritarian regimes like Egypt are not efficient state machines; they are brittle, opaque, and economically extractive. Their decision-making processes are distorted by fear, elite rivalry, and lack of institutional accountability. This leads to poor public service delivery, reactive crisis management, and spiraling debt. Outcomes that ultimately undermine both internal stability and external reliability. Europe should support and invest in comparative policy research, public diplomacy, and political education that highlights these structural weaknesses, not just ethical violations.

In short, authoritarianism is not only unjust, it is unsustainable. Countering authoritarian admiration means showing not only what such regimes suppress, but what they fail to deliver: competent governance, inclusive development, and real long-term stability.

[1] Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, The Gambia, India, Iraq, Italy, Lebanon, Lithuania, Pakistan, Romania, Senegal, Sierra Leone, the Solomon Islands, South Korea, Taiwan, Tanzania and the USA

Downloads